Heiresses and the “Rules” of Quartering

Contributed by Hugh Wood

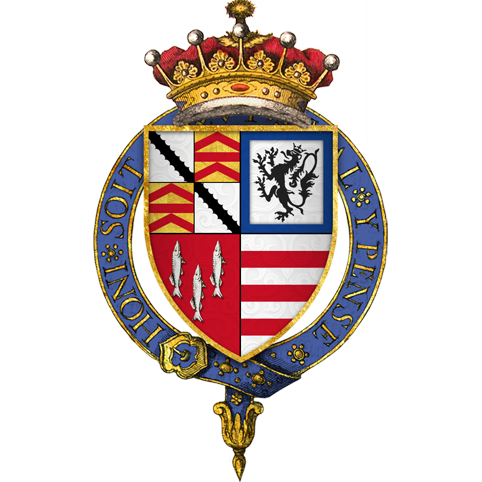

The main purpose of this article is to demonstrate that things are often much more complicated than they seem; that some of the apparent “rules” of heraldry clearly didn’t exist in medieval times, and that even later they were not uncommonly ignored or circumvented. A coat of arms of Henry Radcliffe (d1557) 2nd earl of Sussex, now in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow is an excellent case study – see opposite.

There will probably be readers of this article who know much more about this subject than the writer. We’d welcome helpful comments which can be left at the end of the article.

Introduction

Following the Rule

Edmund Mortimer (d1381), 3rd earl of March married Philippa, Countess of Ulster, who was heiress of her father Lionel, Duke of Clarence. From that time the earls of March quartered their arms, leaving the paternal coat of Mortimer in quarters 1&4

It is not uncommon to see quartered arms reversed, when the arms are being used by, or specifically refer to, a wife or widow. In this example at Cirencester the Mortimer and Burgh quarterings are reversed, but this would be for some specific reason and didn’t affect the quartered arms that were passed down to later generations.

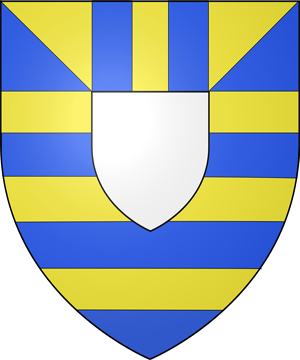

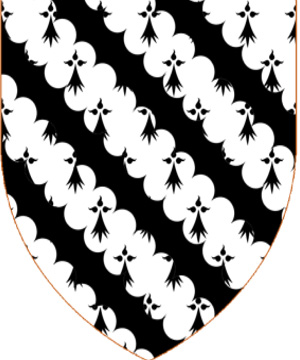

Mortimer

de Burgh

Mortimer quartering de Burgh – the arms of the 3rd, 4th & 5th earls of March

de Burgh quartering Mortimer – for a Countess of March

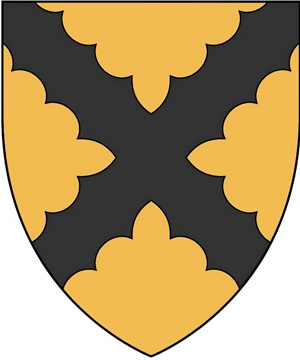

Sir Hugh Burnell KG (d1420) 2nd Baron Burnell

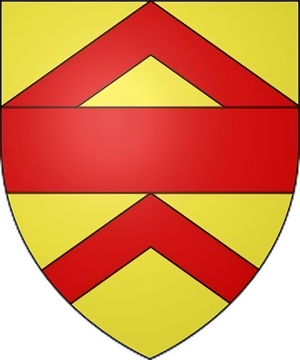

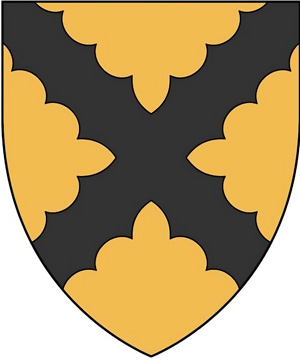

It can be confusing to find that the pattern outlined above was not at all standard practice, especially in the medieval period. Sir Hugh Burnell married, as his second wife, Joyce (aka Joan) Botetourt (d1406) 3rd Baroness Botetourt in her own right. His garter plate in St George’s, Windsor shows his coat of arms following his nomination in 1406. This shield doesn’t fit the usual pattern.

Instead of placing his own arms in quarters 1&4, Lord Burnell has given his wife’s arms the priority. This was not uncommon when a man felt that his wife’s arms were in some way more important or significant than his own.

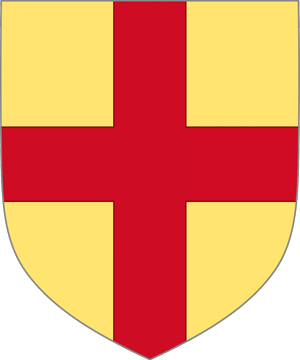

Burnell

Botetourt

Sir Hugh Burnell

The Radcliffes

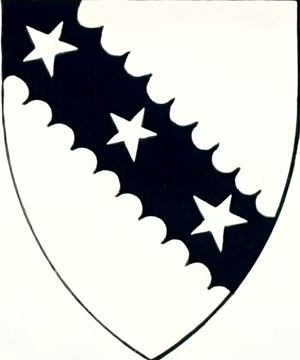

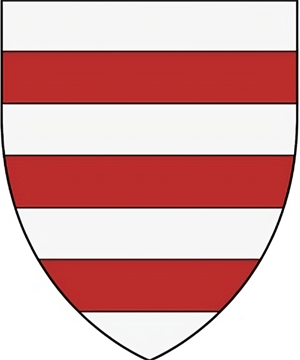

The basic arms of Radcliffe. Radclyff, Ratcliffe etc are easily recognised being argent a bend engrailed sable.

Several other versions of the Radcliffe arms exist, differenced for cadency.

In 1212 William Radcliffe gave one quarter of the Manor of Edgeworth to Robert de Entwistle when he married William’s daughter, and so the Entwhistles modelled their arms on those of the Radcliffes. This is an example of feudal differencing.

Radcliffe

Radcliffe

differenced for cadency

Radcliffe

differenced for cadency

Entwhistle

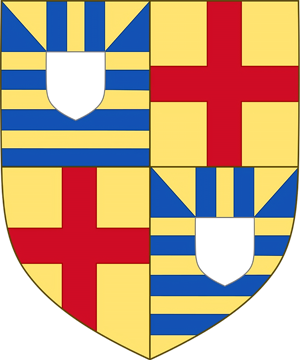

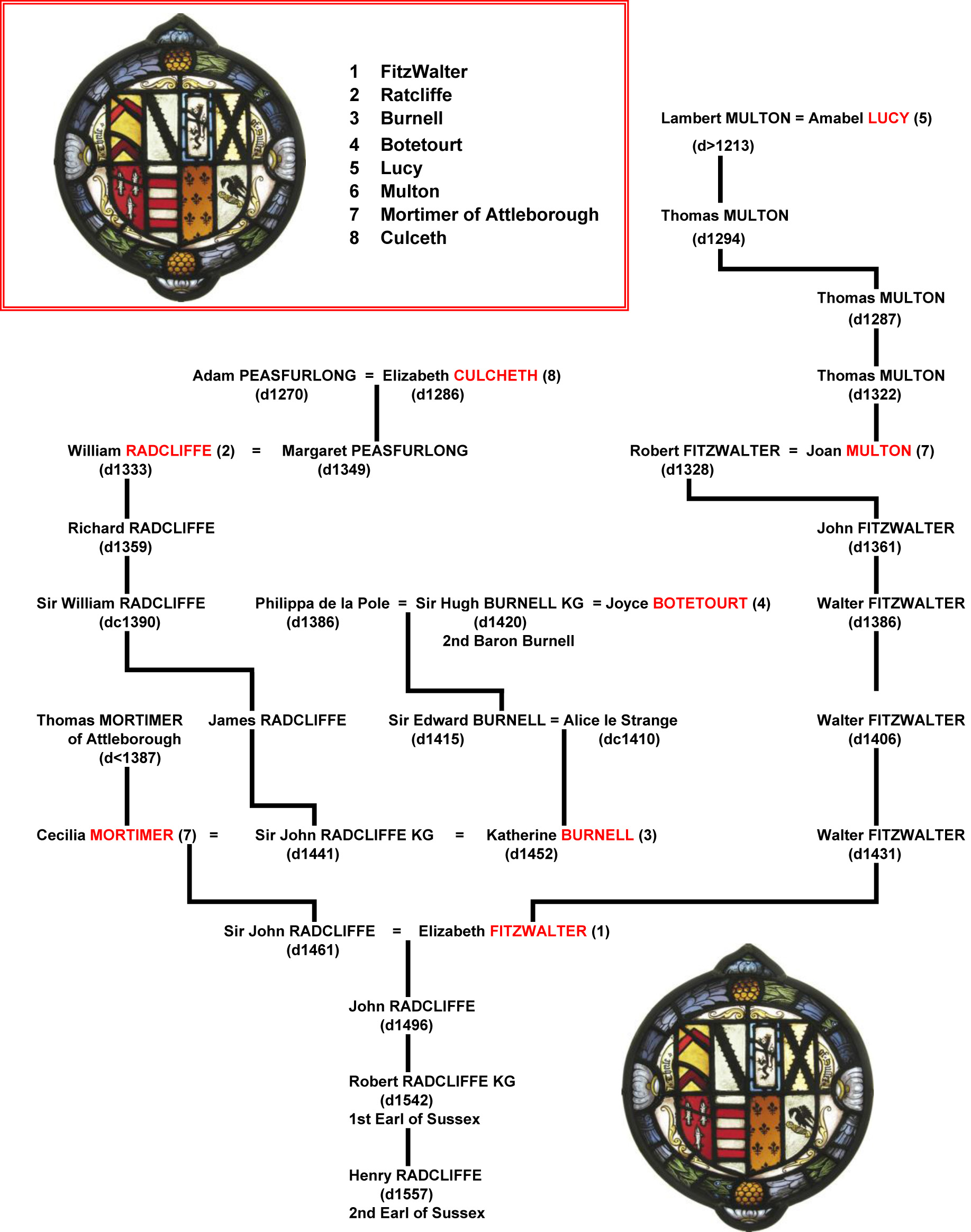

Arms of Sir Henry Radcliffe (d1557) 2nd earl of Sussex

As stated earlier this example of the earl’s arms is in the Burrell collection.

Quarter 1

FITZWALTER

Quarter 5

LUCY

Quarter 2

RADCLIFFE

Quarter 6

MULTON/MOULTON

Quarter 3

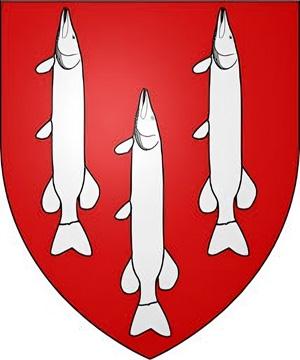

BURNELL

Quarter 7

MORTIMER of Attleborough

Quarter 4

BOTETOURT

Quarter 8

CULCHETH

Note how the Fitzwalter coat of arms in the window lacks the fess gules that is normally between the two chevrons. But the most interesting thing about this coat of arms is how the various quarterings have been added. The usually accepted “rule” is that the arms in quarter 1 are paternal arms, normally identical with the surname of the holder of the arms. Quarters are then added in the order in which they were added to the paternal coat. When a new quartering is added, it can bring in with it any quarterings already associated with it, ie from previous heraldic heiresses.

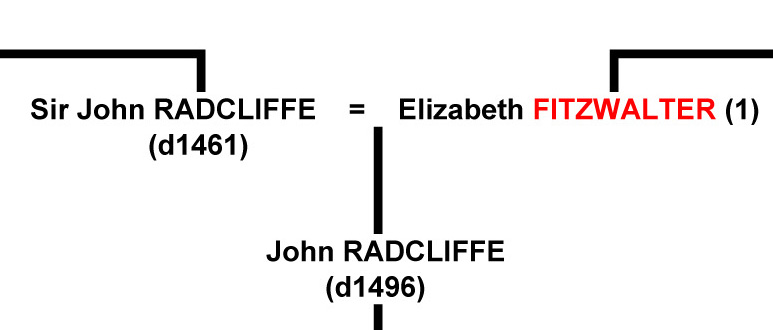

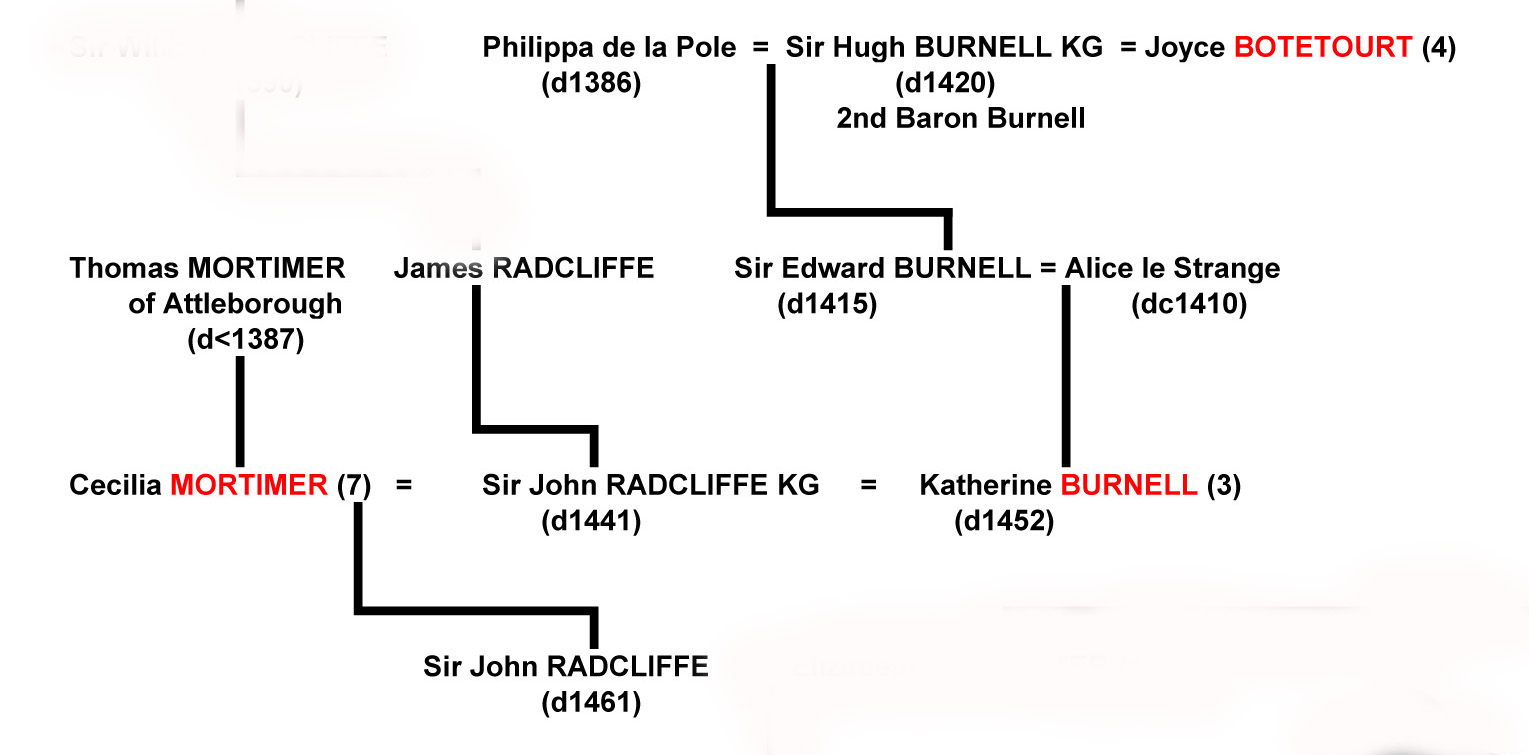

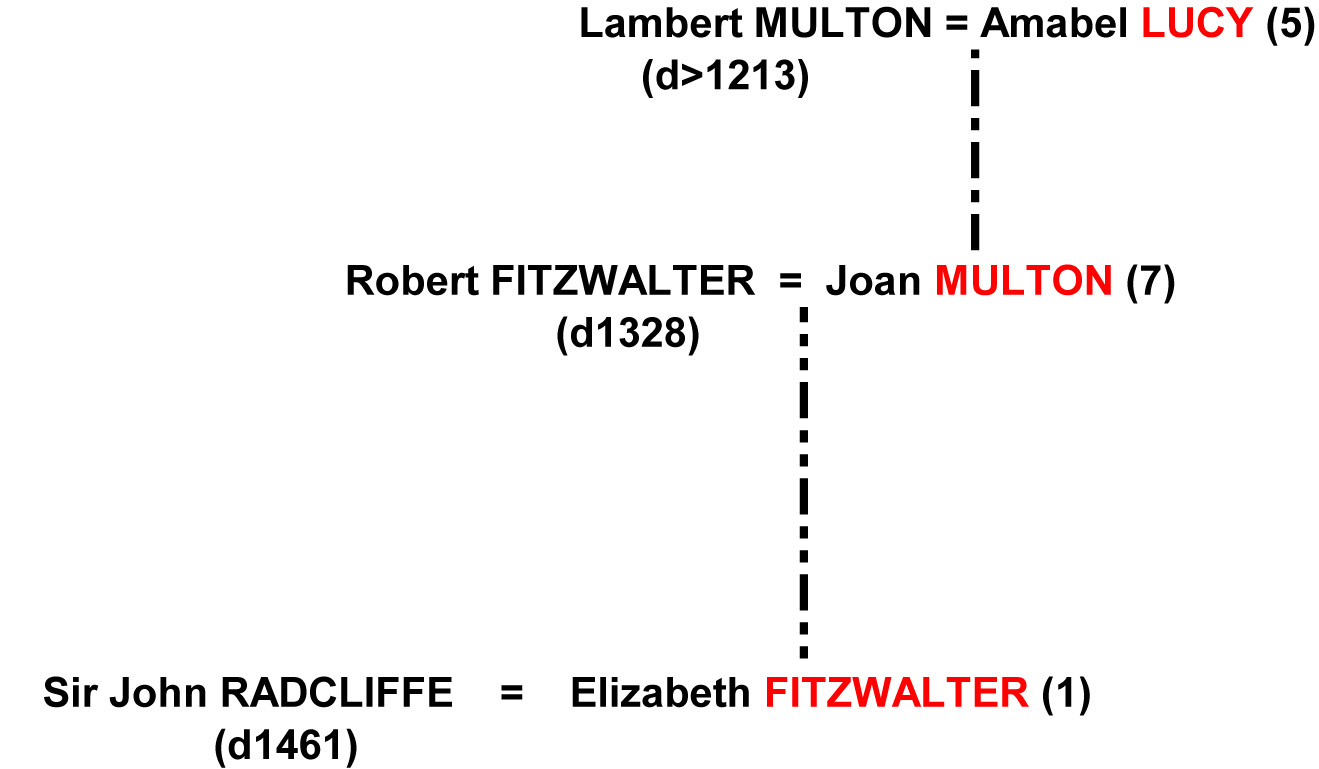

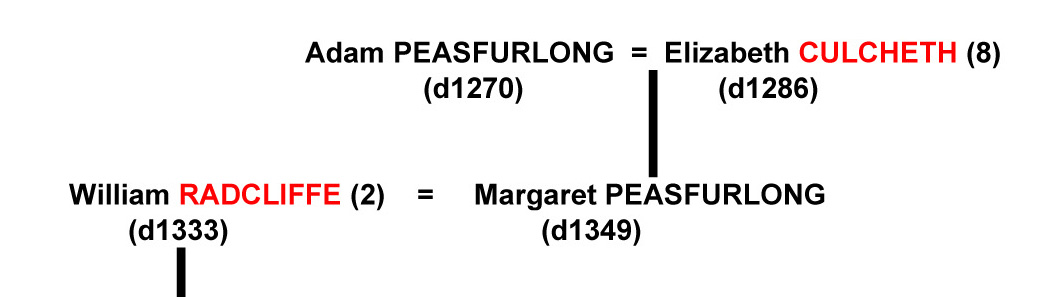

The skeleton family tree below shows the places where the seven quarterings were added to the Radcliffe arms, or to their sub-branches. It’s complicated, but you’ll see immediately that the quarterings do not follow any obvious pattern. The number of each quartering is given next to the name.

Careful study of this pedigree throws up are a number of very interesting points. To make it easier to follow, sections of the pedigree have been reproduced separately.

The Radcliffe arms are not in quarter 1

Some of the quarterings are from non-ancestors

When an heiress brings quarterings with her

A missing quartering?

Variations in the Arms of the Earls of Sussex

As usual, the coat of arms of the 2nd earl of Sussex in the Burrell Collection is not the whole story. Later earls were to add further quiarterings, but they do not concern us here. However two variants appear on the garter plates of the 1st and 2nd earls.

The garter plate of the 2nd earl reinstates the Radcliffe arms in quarter 1, and transfers Fitzwalter to quarter 2. Otherwise it is identical to that in the Burrell.

The arms on the garter plate of the 1st earl are more interesting. He dispenses with Botetourt, Mortimer and Culcheth, concentrating on Burnell and the Fitzwalter-related quarters of Multon and Lucy. Following the marriage of Sir John Radcliffe to Elizabeth Fitzwalter, the barony of Fitzwalter descended through the Radcliffes, so the Fitzwalter ancestry was very important. In these arms, quarter 1 is made into a grand quarter with Radcliffe quartering Fitzwalter. This seems much the most effective way of emphasising the importance of the Fitzwalter baronry.

2nd earl

1st earl

Leave A Comment