A Mortimer Puzzle

Contributed by Hugh Wood

These dramatic Mortimer arms are to be found in an early 16th century manuscript in the College of Arms (L9), where they are attributed to a Henry Mortymer. The charge on the escutcheon is of a viper swallowing a person, and the explanation of this device is both interesting and enigmatic. Associated with the Visconti family in Italy, its origins are obscure but are said to go back to the time of the crusades. Here is one suggestion….

Our ancient citizens put all their efforts in making war. What first appears of the army is the banner with the viper; this banner is brought in front of the army and nobody is allowed to make camp if the viper is not first placed above a high tree. This is a privilege of the Visconti, who own this device; it was first given to Ottone Visconti, who took it from the head of a Saracen king after a duel in front of the gates of Jerusalem. Indeed it is painted of a blue colour, with rings and terrifying eyes, as it devours a red Saracen.

The Visconti ruled Milan from 1277 to 1447, so their coat of arms is sometimes described simply as Milan rather than Visconti.

Although it has nothing whatever to do with this strange Mortimer coat of arms, it is worth mentioning that the Visconti family had been briefly linked with the English royal family about 150 years earlier. As all good students of the Mortimers know, Lionel of Antwerp, the second son of Edward III, and his wife Elizabeth de Burgh were ancestors of the later earls of March. Elizabeth died in 1363. Five years later Lionel married Violante Visconti, the 13 year old daughter of the duke of Milan. The wedding was held in Milan and there was a lavish feast of 30 courses of meat and fish. Among the guests were Geoffrey Chaucer, Petrarch, Jean Froissart and John Hawkwood, the infamous mercenary leader. Sadly, Lionel died less than five months later, possibly poisoned by his father-in-law.

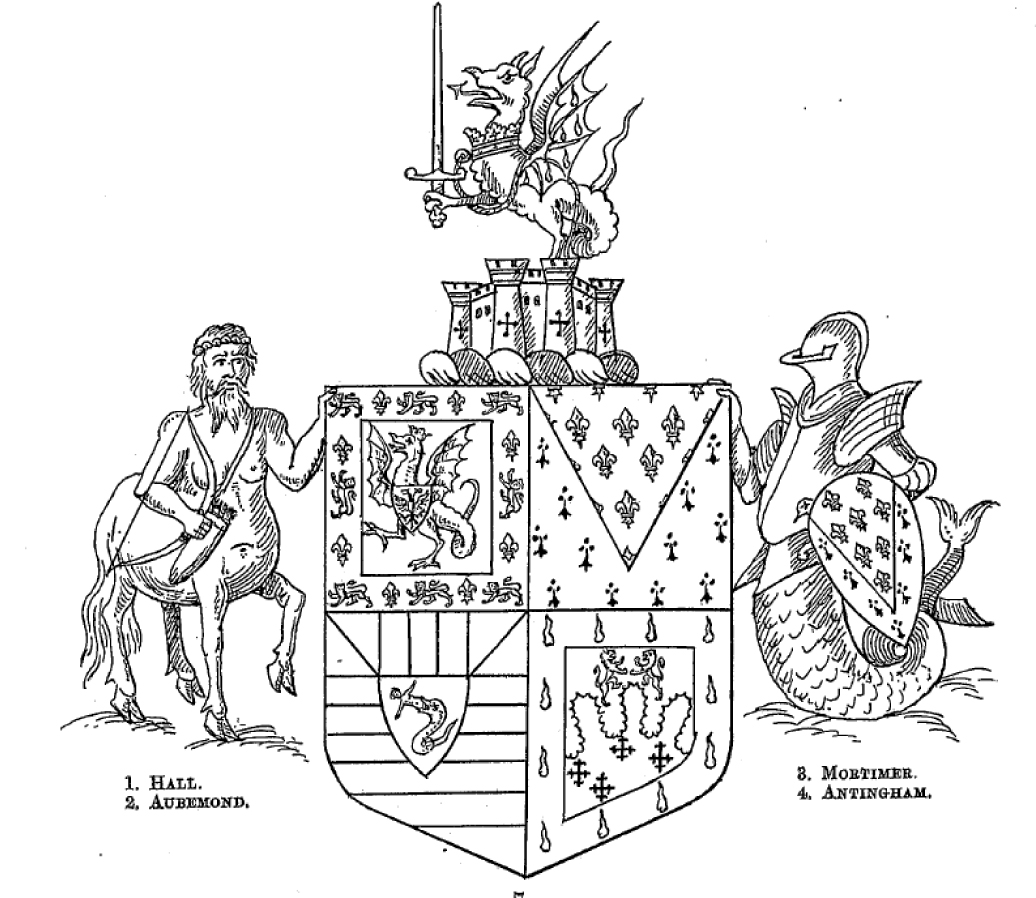

Returning to the Mortimer arms featuring the Visconti badge, another 16th century manuscript in the College of Arms (L1) includes a most interesting shield.

As you can see our Mortimer arms are now just part of a very complicated collection of quarters. In the manuscript they are attributed to an Edward Hall, Gentleman of Grays Inn, Holborn. There is an extensive biography of this Edward Hall on the History of Parliament website. Born in 1496/7, he attended Eton and Cambridge before studying the law. He became an outspoken critic of Cardinal Wolsey and a strong supporter of Cromwell and Henry VIII. He is particularly famous for his vivid day-to-day chronicle of London and parliament, and for writing The Union of the Two Noble and Illustrious Families of Lancaster and York.

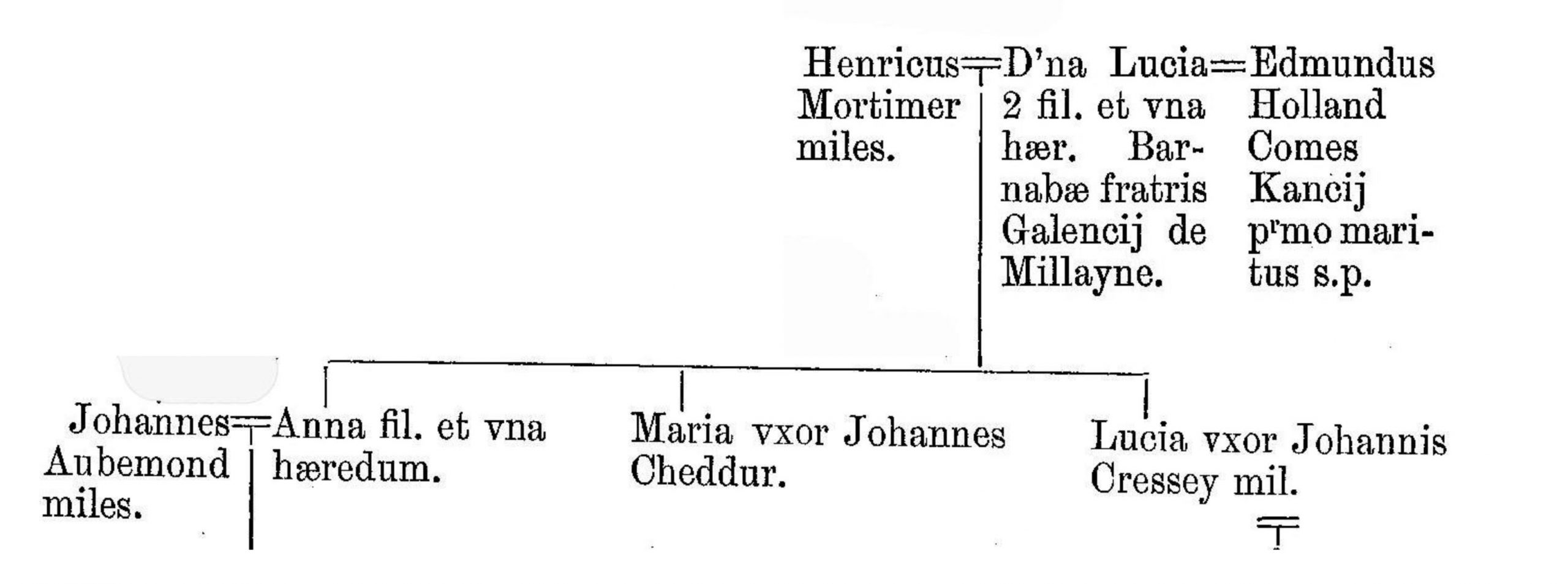

For clues as to the derivation of this coat of arms we need, surprisingly, to go to the 1623 heraldic visitation of Shropshire. The relevant section concerns Hall of Northall, near Kynnersley, which is a village a few miles north of Telford. The associated pedigree links Edward Hall through six generations to the Henry Mortimer we met earlier. Moreover it claims that this Henry Mortimer had been married to a Lucia Visconti and that Edward Hall is descended from them. Hence the Visconti badge in the centre of the Mortimer shield. The achievement of arms opposite is the one given for Hall of Northall in the 1623 visitation of Shropshire. It shows the same four quarters as in the 16th century manuscript but identifies each of them. It is also embellished with a wonderful crest and supporters.

Now we know quite a bit about this Lucia Visconti. She was youngest of the fifteen legitimate children of Bernabo Visconti (d1385) the ruthless lord of Milan. One of Bernabo’s objectives was to secure good dynastic marriages for his ten daughters. As a girl, she’d met Henry Bolingbroke and their marriage was projected. Negotiations ceased, however, when he was banished from England. Lucia was briefly married to Frederick of Thuringia, the future Elector of Saxony, but the marriage was soon annulled on the grounds of non-consummation. In 1407 Henry Bolingbroke, now Henry IV, arranged for her to marry the impoverished Edmund Holland 4th earl of Kent. Their marriage was short and unhappy. Edmund had an affair with Constance of York shortly before his marriage, fathering a daughter who was born after his wedding to Lucia. He died in battle just 20 months later. As her husband had big debts and Lucia’s dowry was never paid, she remained a poor widow, as Countess of Kent, till her death in 1424. She had no children.

Everything in the paragraph above seems to be true. In Lucia’s biography there is no mention of a Henry Mortimer, or of any children. But here is what it says in the 1623 Heraldic Visitation of Shropshire. It acknowledges her childless marriage to the earl of Holland, but suggests an earlier marriage to Henry Mortimer, a marriage that resulted in three daughters Anna, Maria and Lucia.

So who is this Henry Mortimer supposed to have been? The fact that the tinctures of his Mortimer arms are gules and or rather than azure and or immediately suggests that he was one of the Mortimers of Chelmarsh in Shropshire, as that is how they differenced their arms from the main branch. It was Hugh Mortimer (d1273-4), a younger son of Ralph Mortimer of Wigmore (d1246) who was the first Mortimer of Chelmarsh. This branch existed until Hugh Mortimer was killed at the battle of Shrewsbury in 1403. Although there was more than one Henry Mortimer of Chelmarsh, we don’t know of any who could conceivably been married to Lucia Visconti.

Pulling everything together, there is no evidence of Lucia ever having been married to a Mortimer, or that she ever had any children. Additionally we can’t identify a possible Henry of Chelmarsh. So we have to come to the conclusion, rather reluctantly, that Edward Hall’s coat of arms was largely THE STUFF OF FANTASY!

Great story, but oh what a shame we can go no further. I think I’ll insert the arms into my collection though as a “mystery”.

Alan

An interesting article, but have you seen https://murreyandblue.wordpress.com/2025/01/13/six-or-seven-marriages-but-only-one-husband-or-two/ ?

Fascinating research and thanks for sharing

Which just goes to show that mediaeval records aren’t always quite as accurate as they appear!