Some Augmentations of Honour awarded by Richard II and Henry VIII

Contributed by Brendon Clarke

During the present age, whether or not a grant of arms made by the Office of The Lord Lyon in Scotland or the College of Arms in London is an honorific must be debatable. Unlike an MBE and similar decorations that are distinctions presented for merit or service without being either asked for by the recipient or invoiced, grants of armorials from the Lord Lyon or the Heralds’ College must be applied for by the person who wants them – and they have to be paid for. In the interests of elegance requests for a grant are dressed up by being known as “petitions” and the grant furnished by Letters Patent after payment, is called an “award.” In 2024 the fees payable to the College of Arms for a personal grant of arms and crest are £8,950 and they tend to increase every January. Accoutrements to be registered alongside an escutcheon and crest, such as a personal badge or the exemplifying of a personal standard, necessitate further payments, though the new armiger’s right to have such a freshly registered flag made and hoisted is grandly implied. The Office of The Lord Lyon likewise charges thousands of pounds.

Some say therefore that coats of arms granted nowadays are elitist conceits. Meanwhile “petitions” for an award of armorials from anyone describable as respectable and also willing to be guided in apt design by an Officer of Arms, (herald) along with their having an ability to pay the fees, are unlikely to be refused.

Augmentations of Honour

Augmentations of honour are usually only added to existing armorial bearings. They are visual tributes paid by rulers to established armigers who have done something outstanding, or gained especial favour for some other reason. By adding clear indications of distinction to them, augmentations of honour enhance armorials already previously awarded, or that have long been recognised as genuine. They are patently actual honorifics as they are rare marks of conferred accolade, though they have no set format. They usually manifest as additional charges awarded by Royal Warrant to recipients’ shields; or else their crests, badges or supporters.

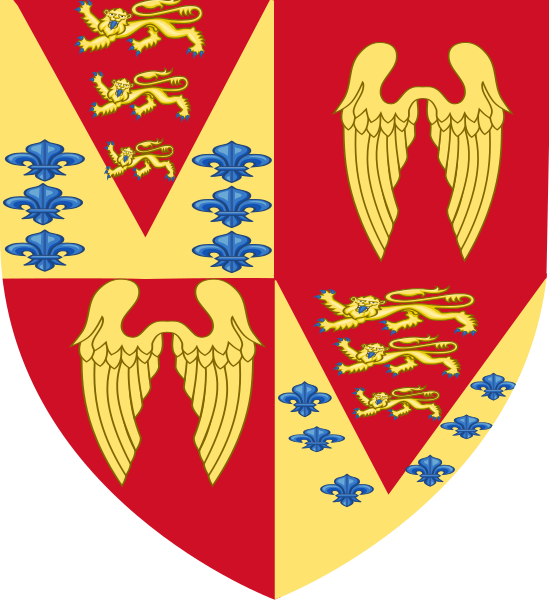

After marrying Jane Seymour, Henry VIII awarded an augmentation of honour to her father. This new design was to be quartered with the Seymour arms, demoting them to quarters 2&3.

Such awards are sometimes inheritable, with descendants of recipients being warranted to display them on their own inherited arms, so as to visibly commemorate and celebrate their ancestor’s distinction. Famously for example in 1513 the Scots were devastated by the English at the Battle of Flodden, the King of Scotland being slain by an arrow. Following the battle, King Henry VIII awarded an augmentation of honour to the noble commanding the English, the seventy-years-old Earl Marshal of England, Sir Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey. This was an approximation of the arms of Scotland that was to be added in a place of particular notice, but with the ‘Lion of Scotland’ shown on the augmentation as slain.

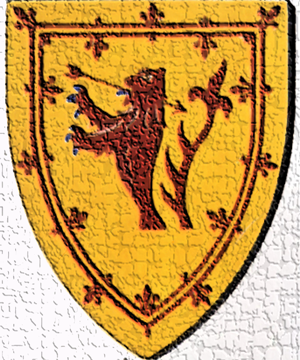

The approximation of the arms of Scotland for the purposes of the honour was formed as a red demi-lion rampant pierced through the mouth with an arrow, bordered by a double tressure also in red; charged onto a small gold shield. The king clearly specified this award as being for the earl’s merit – and also to his posterity, which meant that his descendants would be entitled to display it on their inherited bearings. He also created the earl as Duke of Norfolk the following year, reinstating him to an entitlement forfeited long before by his father. 1513 was not a good year for “The Auld Alliance” between Scotland and France because King Henry himself had led a successful military expedition into France with battle and siege triumphs over the French around the same time as the Duke of Norfolk’s victory over the Scots at Flodden.

These are Earl Thomas Howard’s bearings as they were before the Flodden augmentation.

This is the Flodden augmentation –

image courtesy of The Heraldry Society

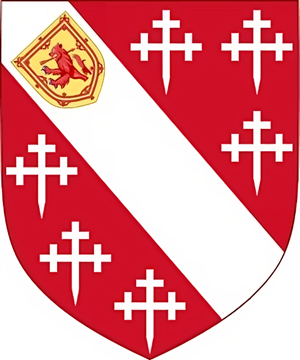

Earl Thomas Howard’s shield complete with the augmentation.

Differences

The image opposite displays a shield of the Beaufort dynasty that descended from Edward III’s son, Duke John of Gaunt in the late 14th century. It is well known that the Beauforts were initially illegitimate. Subsequent to agreeing their legitimisation declared by Pope Boniface IX, Richard II allowed them to discontinue their original armorials and use the royal arms instead, “differenced” with a bordure compony” in John of Gaunt’s livery colours. Thus the subsequent bearings of Beaufort are an exemplifier of ‘differenced arms.’

Differences are not as rare as augmentations, and, in the medieval period, they resulted in entirely new coats being created, even though they simultaneously alluded to those they were differenced from. Various branches of the Mortimer dynasty for instance bear armorials that have been deliberately “differenced” from one another; while usually visibly referencing the senior line’s unmistakeable charges. Certain bearings found on shields are sometimes in consequence blazoned as being “for difference.”

Augmentations awarded for merit or royal favour complement the arms they are added to, whilst differences create distinctions between coats of arms that would without their inclusion, be identical. Problems can arise when a shield is viewed without information having been offered in relation to it. Both augmentations and medieval differences can usually only be discerned for what they are by dint of acquaintance with the arms they have transformed. Some augmentations, though, feature elements from royal armory and these can explain their raison d’être by appearing on the escutcheon of a non-royal personage.

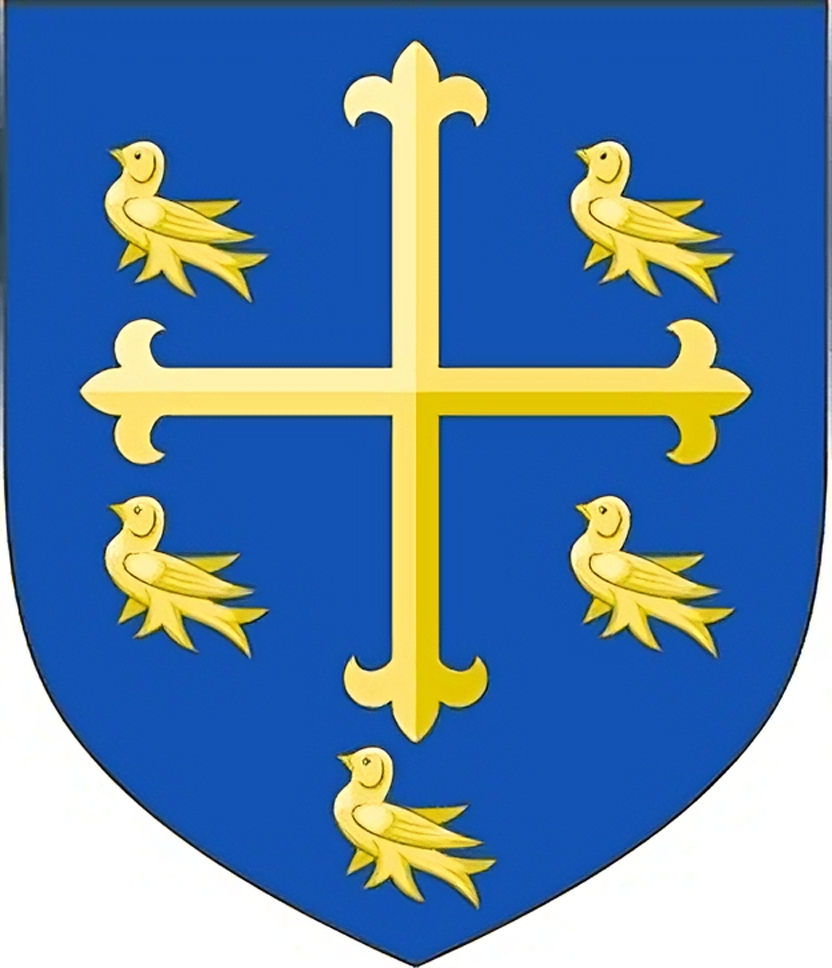

Edward the Confessor and Richard II

The first recorded augmentations of honour, as distinct from differences, are based on the attributed arms of King Edward, ‘The Confessor’ of the Saxon House of Wessex. He lived before heraldry, as we recognise it, developed and is not known to have used armorials at all. Two hundred years after his lifetime, however, thirteenth-century heralds attributed a set of ascribed bearings to all of the successive heads of the later House of Wessex, including ‘The Confessor’ who had been canonized by then. He was assigned as having borne a blue shield charged with a gold cross surrounded by five doves, which were also gold. That the birds depicted on his ascribed armorials are doves has been disputed, and today most images show martlets.

Azure a cross fleury within an orle of ‘doves’ Or

When Richard II was sovereign in the latter part of the thirteen-hundreds, he augmented his own quartered bearings by impaling them with the arms ascribed to the Confessor whom he prized as the greatest saint. King Richard placed the augmentation that he had conferred upon himself in the dexter of the impalement, giving the Saxon saint’s assigned armorials precedence over the ones he had inherited from his grandfather, King Edward III. Despite his arms nowadays being typically shown in this way, he actually used his original, inherited, royal bearings for all but the last four of the twenty-two years he was sovereign and never included the ‘Confessor Augmentation’ onto his seal, although he may have intended to.

Richard II’s Great Seal, his Seal of Majesty used to validate documents of the utmost national importance – as the monarch’s Great Seal of the United Kingdom still does now, remained displaying his original arms only. But he granted, in addition to himself, augmentations to the bearings of a few chosen courtiers who met with his approval, and having married twice he also augmented the armorials of his wives. They were “grace and favour” honours not necessarily earned by outstanding action – but accolades nonetheless. Nearly all of the small number of nobles involved were told to add Saint Edward’s arms to their own as a dexter impalement, in the same way he had. It is not the intention of this article to describe all of the augmentations of honour granted by Richard II or those awarded by Henry VIII, for there is insufficient space, but the deliberate enrichments awarded by Richard II are the first augmentations verified by records. The handful of such awards claimed to have been granted by monarchs before his reign are traditions that lack documented proof.

Richard’s first queen consort, Anne of Bohemia died of plague in 1394 aged twenty-eight, when Richard was twenty-seven. He espoused his second consort Isabella of Valois, a daughter of the King of France, when he was twenty-nine and she was six. She included her dolls in her wedding trousseau. With the augmentation Richard conferred onto them, both his wives’ shields became “tierced in pale” – i.e. three ways vertical. The placement of the “Confessor Award” to the dexter emphasised its status. Richard’s wives displayed their husband’s royal arms, Quarterly France and England, in the middle tierce and placed their father’s, which they were entitled to use, in the sinister section.

King Richard’s bearings are seen to be still displaying ‘France Ancient,’ not ‘France Modern’ as his young wife, Isobella would have been taught to do. The English monarchy did not change the number of fleurs-de-lys on their royal arms to match the French alteration made by Isobella’s grandfather in 1376 until some years after Richard II’s overthrow.

Subsequent to King Richard’s downfall and death, Isabella of Valois was eventually allowed to return to France. Her father King Charles VI arranged a second union for her. The Duke of Orleans was the new groom intended to sweep her off her feet, as it were. A strapping young man all of eleven years old. The union took place when she was sixteen but she died three years later in childbirth.

King Richard also bestowed the Confessor Augmentation, “Azure a cross fleury within an orle of five doves Or” as a dexter impalement upon the arms of his relation, Earl Marshal Thomas De Mowbray. Unhappily, and even in the wake of receiving further honours, Mowbray seriously lost favour with his monarch and was banished from the realm, finally dying in Italy of plague. Nevertheless before his expulsion he had fathered five children by his second wife.

Henry VIII

Waxwork of Henry VIII previously exhibited at Fort Paull, a gun battery he built on the banks of the Humber in East Yorkshire.

A hundred and fifty years later, towards the end of Henry VIII’s reign, one of Mowbray’s descendants, the Earl of Surrey, took it upon himself to include the Confessor augmentation as one of the quarters displayed on his very showy coat of arms. The earl claimed this privilege because his ancestor had been granted the accolade previous to being exiled from the country, although there does not seem to be any record revealing that the award was inheritable.

Henry VIII was by then about fifty-seven and so not of a great age, but he was tormented by illness and sores. Viewing the Earl of Surrey’s adoption of the augmentation through increasingly wrathful eyes, the afflicted king considered the noble’s use of the accolade without royal permission to have been an infamous and clear indication that Surrey was wishing him harm, and plotting to take the throne for himself. Henry therefore had the earl beheaded for high treason. In addition he also decided to execute the Earl of Surrey’s father whom he had also incarcerated; but he died himself, the night before this sentence was to be carried out. The execution was cancelled. The peer whose life was thereby spared was the Third Duke of Norfolk, a son of the Duke of Norfolk to whom King Henry had awarded the Flodden Augmentation, thirty-four years beforehand. As the king’s own warrant had granted the Flodden honour to the duke’s father’s “posterity” the image of the Scottish red lion pierced through the mouth by an arrow could be exhibited on his own bearings. This he continued to do, subsequent to being let out from jail. His descendant, the present Duke of Norfolk and overseer of the College of Arms in London still displays the image of the mortally wounded lion on his splendid, hereditary coat.

Awards conferred by Richard II certainly did not guarantee lasting favour, but augmentations awarded by Henry VIII did not always bring enduring good fortune either, or even lasting life. The Marquis of Exeter, Sir Henry Courteney, for instance, Knight of the Garter, and the sovereign’s cousin, was raised to high and honourable estate, mostly by virtue of having been a friend of the second Tudor king since they were children. As adults Henry augmented Sir Henry Courteney’s armorials by permitting him to use the royal arms, so underlining visually his linkage with the royal family. They were differenced by a bordure and placed as the first of the marquis’s quarterly bearings. Courteney’s eventual fate years later was to be accused, without much evidence, of plotting to supplant Henry on the throne. He was decapitated by a sword on Tower Hill, outside the Tower of London.

King Henry VIII also enriched the arms of all four of his English-born queens, but not those of his two foreign-born consorts. Of the quartet whose armorials he augmented Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard were beheaded and Jane Seymour perished in childbirth. After the monarch himself died, his fourth wife Catherine Parr, whose armorials were augmented, married Jane Seymour’s youngest brother, Thomas. Jane’s eldest brother Edward was appointed as Protector of The Realm when Henry’s heir, Edward VI was still only a child. Catherine Parr’s destiny was to die in childbirth, and eight months later her husband, Thomas was executed by his brother for treachery. Henry VIII of course could not be blamed for that – probably.

Manners

The House of Manners in the male lineage is traceable back to France previous to the Norman conquest. The family moved to England in the wake of the invasion, originally settling in Northumberland.

Centuries after their arrival in this country, Sir Thomas Manners was part of the English invasion of France in 1513. Over the next twelve years he functioned as a knight, jouster and king’s officer in Henry VIII’s household. He assisted at ‘The Field of The Cloth of Gold’ and helped to govern castles around various parts of England. Sir Thomas was subsequently created Earl of Rutland, the sovereign marking his service by awarding him an augmentation of honour inheritable by his descendants. The Manners coat of arms had included a chief gules but now this was replaced by one showing the royal arms – quarterly France and England. Sir Thomas was fortunate: Henry VIII elevated him to be an earl; installed him as a Knight of The Garter and augmented his coat of arms yet he did not chop off his head.

The shields opposite show the Manners’ arms before and after the augmentation. The latter is in the church of All Saints in Bakewell in Derbyshire. The crescent charge for cadency-difference indicates that this is the shield of a second son.

The principal seat of the Manners family became Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire. According to tradition, Sir Thomas’s second son, John Manners tried to court Dorothy Vernon who lived at Haddon Hall in Derbyshire. As the Vernons were Catholics, her father forbade the pair from associating. The anecdote maintains that the young couple eloped to Leicester and married, inspiring the writing of romantic novels about them, plus an opera. It seems Dorothy Vernon’s father eventually relented because he left Haddon Hall and much of his landed estate to her. The stately home that the Vernons had lived in for four centuries thus came into the ownership of the Manners family. The cadency mark indicating a second son on the Manners shield at Bakewell Church refers to John.

The Rutland Arms in Bakewell

The large signboard above the main entrance is based on the heraldic achievements of the Dukes of Rutland. It displays the Manners shield bounded by the symbol of the Order of The Garter, referencing the twelve peers of the dynasty who have been invested into that celebrated institution – eight before the hotel was built and another four afterwards. The horns, hooves, manes and tufts of the shield’s unicorn supporters are golden. Rising from a “duke’s coronet” also gold is a ‘Cap of Authority’ – a chapeau gules turned up ermine. Such armorial headgear supplanting the helmet of rank is rare, though slightly more common amongst Scottish armory. The cap is surmounted by the dynasty’s crest: ‘A Peacock in its Pride’ whilst the motto inscribed onto the ribbon below the escutcheon, “Pour y parvenir” translates as either, “In order to obtain it” or perhaps, “So as to accomplish it.” Whichever translation is preferred, no one seems quite sure what it means. It is described as an “enigmatic” motto and is one of the inscrutabilities of grouse-shooting lords….

Leave A Comment