The Arms of Simon de Montfort (d1265)

Contributed by Hugh Wood

This article is largely reprinted from one that was published in Mortimer Matters No.20 in February 2015, to which has been added an interesting postscript taken from an article of 2021.

Search Google Images for ‘Heraldry Simon Montfort’ and your screen will be covered with images of a white lion with two tails on a red ground – gules a lion rampant double queued argent. From quite early times, this has been the generally accepted coat of arms of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester who died at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, possibly cut down by Roger Mortimer (d1282) himself.

But American MHS member Katherine Ashe believes that this is not Simon’s correct coat of arms and that an error occurred that has been perpetuated over the years. As the author of a four-volume fictionalised biography of Simon, Katherine has clearly immersed herself in her subject, so her opinions must be taken very seriously. The situation is confused somewhat by the fact that Simon’s father, the Simon de Montfort of the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars, clearly used this coat of arms.

Here Katherine sets out her argument and Hugh Wood ventures a tentative response.

Simon de Montfort and the Red Lion Rampant – by Katherine Ashe

Simon de Montfort Senior at Chartres

There has been controversy over just what the colors of Simon de Montfort the Earl of Leicester were. His father, Simon de Montfort known as the Crusader, was famed as a leader of the Fourth Crusade who refused to take part in the sacking of Constantinople and instead led his forces on to Palestine. Highly honored for his integrity, it was he who took command of the French forces after the shameful burning of six-thousand heretics in the church at Bezier, and who then became the leader of the Albigensian Crusade. He is honored by a window of his own at Chartres, which depicts him mounted and in full armor, bearing on his shield the device of a white rampant fork-tailed lion on a red ground.

Because of the ease of access to this image it has become well known – and it has been assumed that this is a depiction of the arms of Simon de Montfort the Earl of Leicester, the champion of modern democracy. It is inconceivable that the Earl Montfort, excommunicated for his support of the democratic movement, and not his father, should be honored by a window at Chartres. The Earl of Leicester surely is not depicted there, and the shield of the white lion may not be his arms.

We aren’t lacking evidence of what his arms actually were. It was common practice for the arms of a son, especially a younger son, to be differenced from those of his father. And indeed Simon’s were. Matthew Paris, the most highly regarded of thirteenth century chroniclers, knew the Earl well and included in his great tome, the Chronica Majora, a personal letter sent to Simon by his nephew in Germany.

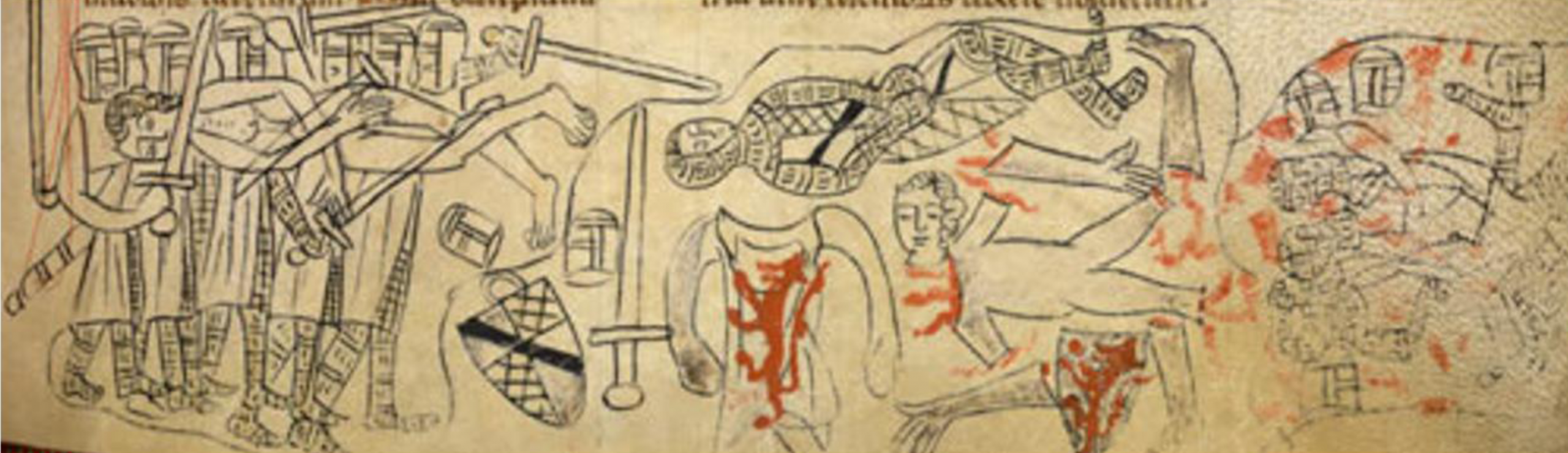

At his monastery at Saint Albans, Brother Paris was one day’s ride north of London on Simon’s route to Kenilworth or Leicester; it is a fair assumption the Earl stopped there regularly. Paris records private information that probably only Simon could have told him. Certainly Paris knew very well what the Earl’s arms were, his flag flying from the inn or the monastery’s guest quarters being a familiar sight. In his illustration in the Chronica Majora Paris depicts the arms of most of England’s principal lords. The arms he shows for Simon de Montfort clear represent a red fork-tailed lion rampant on a white ground. Again, the chroniclers of Saint Albans, in the Flores Historiarum, depict the arms of Simon de Montfort in the illustration of the aftermath of the Battle of Evesham. Simon’s remains appear, dismembered, in the center foreground with his shield beside him. The shield clearly displays the red lion on a white ground.

Nevertheless, since the fourteenth century the Earl Montfort’s arms have been described as a white lion on a red ground, and numerous 19th and 20th century art works show these erroneous arms. One 13th century source, the Glover Roll, describes Montfort’s lion as white on red, but there has long been no surviving original example of this roll and it was heavily “edited” in the 19th century. An error repeated, even when it is repeated for centuries, remains an error. It’s unfortunate that the clear evidence is being laid aside in Simon de Montfort’s Jubilee Year, and even now he is not being honored by the use of the arms that, throughout his life, were his identity.

From the Flores Historiarum – The murder of Evesham, for battle it was none!

A Response to Katherine Ashe from Hugh Wood

It is a brave, or perhaps foolhardy, person who crosses swords with someone as erudite as Katherine Ashe. Over recent months we’ve been playing an almost daily game sending missiles each way across the Atlantic and she doesn’t give in easily! Nevertheless, I’ll explain why I think that both Matthew Paris and the English heralds are correct.

In France and England the same coat of arms is passed down the main male line from father to eldest son so, for instance, Roger Mortimer 1st Earl of March (d1330) had exactly the same coat of arms as his father Edmund Mortimer of Wigmore (d1304). As Katherine mentions, other members of a family needed to difference their arms in some way to distinguish them from those of the head of the family. These differences may be temporary or permanent. The most obvious Mortimer example of a permanent difference is that exhibited by Roger Mortimer of Chirk (d1326) who changed the escutcheon on his shield from argent to ermine. This change survived and it was still cropping up in heraldic quarterings centuries later. Both Roger of Chirk and his brother Edmund of Wigmore signed the Barons’ letter to the Pope in 1301 and their seals have been preserved.

But there was also differencing that was temporary. A man’s eldest son cannot wear the same arms as his father while his father is still alive. When his father dies and he becomes the head of the household he will then wear his father’s arms undifferenced.

It is clear from the window in Chartres, showing the older Simon de Montfort, that the main hereditary Montfort arms were a white lion on a red background. Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester was a younger son and would have differenced his arms from those of his father as was usual. Matthew Paris recorded his arms in about 1244 as a red lion on a white background and, as Katherine points out, he knew Simon well and would not have made a mistake in this.

Simon had an elder brother Amaury who became head of the family when their father died in 1218. There was also another brother, Guy who died in 1220. When Amaury died in 1241, the next in line was his son John. When John died in 1249, however, Simon himself became head of the family and was now entitled to assume the arms of his father, as shown in the window at Chartres. So it seems entirely correct that the coat of arms used for the last 16 years of his life should have been the one that has been handed down to us. Matthew Paris didn’t make a mistake in his description of Simon’s arms, as Simon did not become the head of the family until after Matthew recorded his arms.

Seals attached to the barons’ letter to the Pope 1301

Edmund Mortimer (d1304)

Lord of Wigmore

Roger Mortimer (d1326)

Lord of Chirk

It seems likely, however, that Matthew Paris did make some mistakes. Writing 26 years after the death of the older Simon, he records his arms as identical to those he has for his son – a red lion on a white ground – which we know they were not, from the convincing evidence at Chartres. He seems to have been working backwards from the differenced arms of his son and making false assumptions. Finally, although the illustration of the death of Simon at Evesham, shown above, shows a red lion on a white background, there are other early illustrations of the battle showing Simon wearing the normally-accepted family coat of arms to which he was now entitled, namely a white lion on a red ground. This image on the left comes from the Chronique de St Denis c1340.

Postscript

Writing more recently about the arms of Simon de Montfort, Daria Staroskolskaia says this:

Inaccuracies ….. are often found in early rolls. Thus Matthew Paris described Montfort as bearing a lion without specifying that it has two tails, but he was well aware that it was forked and mentioned it elsewhere. His tinctures are also inverted, as Argent a lion rampant gules. Some other sources also show the lion with only one tail. One might suspect that in the middle of the thirteenth century, before the first armorials, such differences were not considered to be very important.

Heraldry Society Coat of Arms No.238 (2021)

Interesting article. Another famous thirteenth-century knight, Earl William Marshal is also usually shown bearing a shield displaying armorials that have become well known in the modern age, although he did not use them until the second half of his life: – a red lion rampant over an escutcheon divided per pale Or and vert. Yet famed as he was as a successful tournament competitor he did not adopt these arms until he was approaching, or already in, his mid-thirties and close to competing in the final tournaments he took part in. Previous to adopting them he had fought his first ever combat against hostile opponents rather than a training partner wielding the arms of his tutor before going on to make his name and fortune on the tournament circuit using the bearings he was entitled to “inherit” from his father: which were “gules a bend fusily Or. The historians Thomas Asbridge and David Crouch offer between them that Marshal changed to using his red lion shield sometime in the late 1170s, perhaps 1179. He was born around the year 1146.