Dating a medieval carving

at the Swan Inn in Clare

This post is adapted from an article previously published in Mortimer Matters

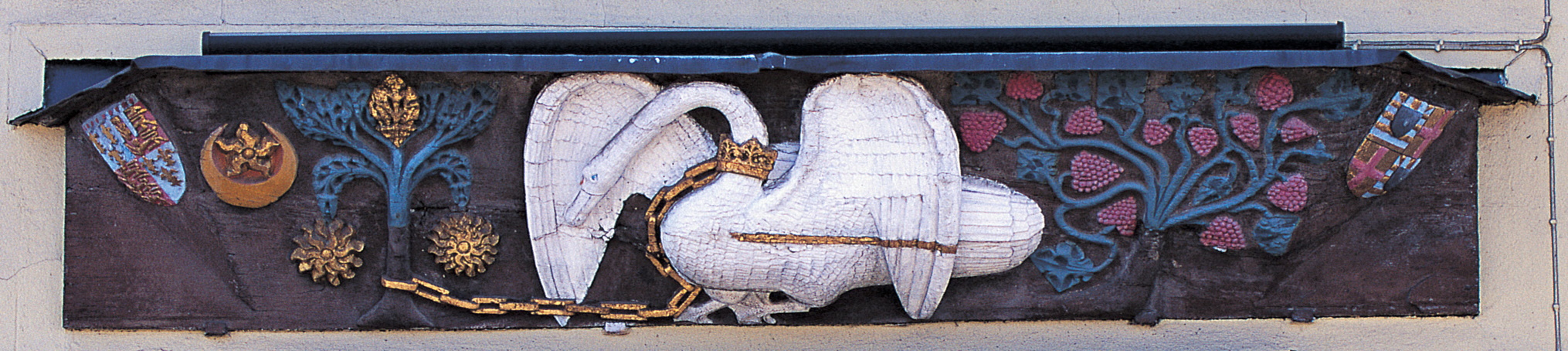

Brightening up the front of the Swan Inn in Clare in Suffolk is this colourful piece of carved wood. Its shape suggests that it was once the sill of an oriel window. The pub itself is thought to date from the 17th century, but the sign is much older, and much more interesting for us, as it came from nearby Clare castle. Looking closely you’ll see the royal arms tucked away at the far left and, balancing them, on the far right, the quartered arms of Mortimer and de Burgh. Dating and understanding this artefact presents is an interesting challenge, but first it’s worth exploring how the Mortimers came to be associated with Clare.

After 1066, the Conqueror awarded Ralph Mortimer estates across the country, so it is tempting to assume that Clare was one of those. But Domesday states that Clare was held by Richard FitzGilbert. Richard’s family continued to hold Clare for a further 128 years. After several alternate Richard FitzGilberts and Gilbert FitzRichards, they finally settled on being called ‘de Clare’.

Gilbert de Clare (d1295) was a strong supporter of Simon de Montfort, who knighted him just before the Battle of Lewes in 1264. Much later, after everything had quietened down in England, Gilbert was still seen as a potential threat to the stability of the crown. King Edward I sought to neutralise Gilbert by betrothing him to his daughter Joan of Acre. They were married in 1290 when she was 18 and he was 46. Joan loved Clare and continued to live in the castle after her husband’s death. She built a new chapel in the priory and is buried there.

Their only son Gilbert was 23 and childless when he was killed at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314. Ownership of Clare then passed to his sister, the famous Elizabeth de Clare (1295-1360). Married three times and with a child from each marriage, she was the founder of Clare College in Cambridge. Her first husband was John de Burgh (d1313) son of the 2nd earl of Ulster, and Clare subsequently passed to their granddaughter Elizabeth de Burgh, Countess of Ulster, who married Lionel the second son of king Edward III. Both Lionel and Elizabeth were buried in Clare Priory. With the marriage of their only child Philippa to Edmund, 3rd earl of March, Clare passed to the Mortimers.

Returning to the carved sign at the Swan Inn, there are a couple of strange things about the Mortimer coat of arms. Firstly, the inescutcheons are black rather than silver. That’s easily explained: it’s not uncommon for silver to degrade to black over time and it was probably repainted black in error. More problematical are the round knobs or rings in the centre of each inescutcheon. It is tempting to assume that this could be a cadency mark, indicating a younger son, but the lack of a suitable candidate seems to rule that out. These marks remain a mystery.

The quartered arms of Mortimer and de Burgh could conceivably relate to Edmund (d1381) the 3rd earl of March, Roger (d1398) the 4th earl, or Edmund (d1425) the 5th earl. As owners of Clare the Mortimer arms on the Swan Inn must surely represent one of them.

The other shield in the display shows the royal arms and this is the key to explaining and dating the carving. The arms in the 1st and 4th quarters are called France Modern. Previously France Ancient had a blue field sprinkled or powdered with fleurs-de-lys but, in 1376, Charles V reduced these to just three. In England the change wasn’t implemented till around 1411, however, so these arms at Clare won’t be much earlier than that.

Of greater significance is the blue label across the top of the shield. A plain label on the royal arms is used exclusively to indicate the heir to the throne, and the only Prince of Wales after 1411 who was a contemporary of the earls of March was Henry, later king Henry V.

The reason why the arms of the Prince of Wales should be on this carving with those of Mortimer is not instantly obvious, but becomes clear when we look at dates and the documentary evidence. When the 4th earl died in 1398 his son Edmund was only six and, as was customary, all his estates reverted to the king. He could do what he wished with them, until they could be given back to Edmund when he reached adulthood. In the National Archives is a manuscript dated c.1408 which explains what happened. King Henry IV granted Clare to the prince during the minority of Edmund Mortimer, 5th earl of March and this carving on the Swan Inn appears to have been done during that period.

On becoming king in 1413, Henry V granted Edmund all his estates, which gives a very small window indeed for this carving to have been relevant, namely 1411-1413. Of course it’s a long time ago and the date could easily be a few years either side of this narrow range.

Even though they held multiple lordships, in England, Wales and sometimes Ireland, Clare and its castle clearly meant a lot to successive owners. They continued to support the priory and when the 5th earl of March died in Trim in Ireland, his body was brought back to Clare priory, for burial alongside some of his illustrious non-Mortimer ancestors.

Thanks Hugh for this fascinating explanation and research.

This looks like the base of an oriel window. I can think of other similar carved oriels in Parham and Halesworth. Contact me if you need to see these. Timothy Easton