Problems with a neurotic Richard II

Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March (d1398)

and his uncle Sir Thomas Mortimer (d1403)

The lives of these two Mortimers were closely linked. Sir Thomas Mortimer played a significant role in some of the most momentous events in the reign of Richard II. His nephew, Roger Mortimer the 4th Earl of March, was just 24 when he was killed in a skirmish in Ireland. It is convenient to combine both their stories into a single narrative.

Sir Thomas Mortimer was a younger son of Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March. Though he is thought by some historians to be illegitimate, he was certainly brought up as one of the family. By the time he was 30 he was an experienced soldier and had been knighted. His older brother Edmund, 3rd Earl of March, lost his wife in 1378 and then died himself in 1381 at the age of 29 leaving his young family as orphans. At the time of his death Roger, his eldest son, was only seven, and his uncle Thomas took on the role of father-figure. The two remained close throughout their lives. Roger’s father had been Lord Lieutenant of Ireland with his brother Thomas as his deputy. On his death, Richard II inexplicably appointed the new seven-year-old earl to replace his father, but then made Thomas the Lord Deputy and Lord Chief Justice.

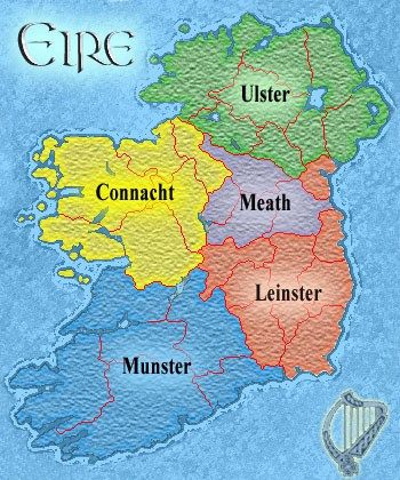

For two reasons, the young Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, was a person of great significance. Firstly, he was very rich indeed. From his father he inherited the vast Mortimer lands in Wales, the Welsh borders and Ireland, while from his mother he inherited more major estates in England as well as the earldom of Ulster and the lordship of Connaught in Ireland.

Of course, as a minor, Roger would not be able to enjoy possession of his estates for many years and the wardship of his lands was initially split between a number of minor figures. Unhappy with this arrangement, a group of magnates objected and, in 1383, his Mortimer estates in England and Wales were granted to a group that included Roger himself, with the earls of Arundel, Northumberland and Warwick with Lord Neville. Having returned from Ireland, Sir Thomas Mortimer was appointed as Steward of the Mortimer estates, a task which he performed very successfully.

The Provinces of Medieval Ireland

Richard II

Even more important than his wealth, however, was the fact that Roger was the eldest grandson of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, the second son of Edward III. As such he was a potential successor to the childless king Richard II. There is evidence that Richard publicly named him as his successor in 1386. Although the king may not have intended this seriously, and never seems to have repeated it, the possibility of Roger becoming the next king was certainly discussed openly.

Richard II’s reign was not going smoothly. Still a teenager, his critics believed that he was being manipulated by favourites at court including Robert de Vere, a highly unpopular man whom he created Duke of Dublin. In 1386, when the Chancellor, Michael de la Pole, asked parliament to approve swingeing new taxes for the defence of the realm, they refused and demanded his removal. Humiliated, the king eventually had to climb down, the Chancellor was sacked and a commission was set up to review the royal finances for a year. Robert de Vere and Michael de la Pole thought it wise to escape to the Continent.

The main opposition to the king came originally from his uncle Thomas, Duke of Gloucester and also from Richard Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel and Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, two men whose hands were greatly strengthened by their wardship of wealthy Mortimer estates. These three original leaders were later joined by Henry Bolingbroke, Earl of Derby and Thomas Mowbray, Earl of Nottingham and together they formed the group known as the Lords Appellant. Sir Thomas Mortimer identified strongly with this group and was popular with them.

Having been put down and embarrassed by parliament, the king now travelled around the country mustering support. He installed Robert de Vere as Chief Justice of Chester with the intention of creating a loyal army based in Cheshire. On his return to London he was confronted by Gloucester, Arundel and Warwick who formally presented an appeal of treason against de Vere, de la Pole and several others.

While the king played for time, de Vere marched south at the head of a force of some 4,000 men. But they were surprised and routed on 19th December 1387 at Radcot Bridge near Oxford by a force led by the Duke of Gloucester and the Earl of Derby. De Vere escaped and his troops surrendered. There was little bloodshed, but when Sir Thomas Molineux, Constable of Chester Castle, attempted to escape, Sir Thomas Mortimer caught and killed him, ignoring his pleas for mercy.

The original Radcot bridge

Robert de Vere escaping to the Continent

The Lords Appellant were now in control. Leaving Richard II in place as titular head, they took revenge on the former favourites in what became known as the Merciless Parliament: six were executed and de Vere and de la Pole were sentenced to death in their absence. They appointed Sir Thomas Mortimer as Justiciar of Ireland, but the king somehow managed to block that appointment. Richard never forgave the Lords Appellant for all this and bided his time. Over the next nine years he quietly rebuilt his position and increased his power.

Luckily for Roger Mortimer, the 4th Earl of March, he was too young to be involved in these events or to be tainted by them. Married at 14, he was knighted in 1390 at the age of 16. A couple of years later he was again appointed as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, but was unable to go there immediately. By 1394 he’d been granted livery of all his lands and had served on an embassy to the Scottish borders. That same year, when the king went on his first expedition to Ireland, both Roger and Thomas went with him. For Roger, there was a lot riding on this expedition: he needed to recover control of the his estates in Meath, Ulster and Connaught, some of which had been quietly reclaimed by native Irish leaders. Achieving a permanent settlement proved very difficult, however. In 1395 he was appointed Lieutenant in those three areas and most of the rest of his short life was spent in Ireland, supported by his uncle.

By 1397 Richard II felt secure enough to wreak vengeance on those who had humiliated him and executed his closest friends and supporters. He had Arundel, Warwick and his uncle Gloucester arrested: Arundel was executed, Warwick was imprisoned for life and Gloucester died while awaiting trial, presumably murdered. Sir Thomas Mortimer was high on the revenge list and his nephew Roger was ordered to arrest him in Ireland, but probably colluded with him in making his escape. Thomas was declared a traitor and had all his lands seized. He died six years later in Scotland.

Now 23 years old, Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, was a dashing figure. In January 1398 he attended a parliament called by the king in Shrewsbury. Attractive, brave, open-handed and largely untouched by the turmoil in England when he was younger, he must have made a striking contrast with the 30-year-old weak, ruthless and childless Richard II. According to Adam Usk and the Wigmore Chronicle, Roger was met at Shrewsbury by a huge crowd of enthusiastic supporters wearing his livery colours. Despite this popular adulation he conducted himself circumspectly.

Back in 1394, with Richard II still childless, the king’s uncle, John of Gaunt, had requested in parliament that his son, Henry Bolingbroke, be recognised as heir to the throne. When Roger Mortimer strongly objected on the grounds that his claim was the stronger, the king refused to allow the subject to be discussed. While Roger was never awarded high status at court, his popularity and lineage clearly worried the king.

Seal of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March and 6th Earl of Munster – Mortimer quartering de Burgh

Mortimer Castle, Westmeath

According to Adam Usk, Richard now set about plotting Roger’s downfall. If he had aided his uncle Thomas to escape, then he was also a traitor. Earlier in 1397 his official position in Ireland had been renewed for a further three years, but it was now announced that it was to be abruptly terminated in five weeks’ time. His brother-in-law Thomas Holland, now Duke of Surrey, was dispatched to arrest him and take over. But this was not to be. On 20th July 1398 he was killed in a skirmish with the Irish near Carlow. The Wigmore Chronicle says that he was dressed in Irish clothes and not recognised. His body was brought back to Wigmore Abbey for burial. The early death of this popular great-grandson of Edward III certainly cleared the way for Henry Bolingbroke’s usurpation of the throne the following year.