Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March

For three years “Ruler” of England

Executed in 1330

In this series of brief articles about the Mortimers of Wigmore, we now come to the most powerful and colourful member of this illustrious family. Soldier and major landholder in England, Wales and Ireland, he served as a loyal supporter and lieutenant of king Edward II until circumstances led him into rebellion, surrender and a sentence of life imprisonment. Escaping from the Tower he fled to France where he forged a close alliance with Edward’s discontented queen, Isabella. Together they accomplished the downfall of the king and Roger became the effective ruler of England for almost 4 years, during the minority of the new king Edward III. Unfortunately power went to his head and, overreaching himself, he was executed for treason at the age of 43.

Roger inherited the lordship of Wigmore in 1304 at the age of 17. Three years earlier, he had been married, at Pembridge in Herefordshire, to Joan de Geneville, the 15-year-old granddaughter and heiress of Geoffrey de Geneville. Geoffrey was one of the ‘Savoyard’ Frenchman who came to England in the train of Henry III’s queen, Eleanor of Provence. He proved to be both talented and loyal and the king greatly enriched him by arranging for him to marry the heiress Maud de Lacy. So, by his marriage to Joan de Geneville, Roger Mortimer gained extensive estates in Ireland and the Welsh Marches, including Trim in County Meath and the great castle at Ludlow, just 8 miles from his ancestral home at Wigmore.

Pembridge church today

The great castle at Trim in Co. Meath

The Mortimers already held lands in Ireland through the marriage of Roger’s grandfather to the heiress Maud de Braose. By his own marriage Roger became one of the principal lords in Ireland and much of his early career was concerned with Irish affairs. As far as we know, he was the first lord of Wigmore to actually set foot in Ireland, which he visited first in 1308.

Roger was very close to his uncle, the warlike Roger Mortimer of Chirk, and in 1314 both of them were with Edward II on the Scottish campaign which resulted in the ignoble defeat at Bannockburn. The younger Roger was captured, but released by the Scottish king, Robert the Bruce, who tasked him with returning king Edward’s privy seal and royal shield to him.

Edward II’s humiliation at Bannockburn had been unexpected and traumatic for the English. Buoyed by his great victory, Robert the Bruce saw an opportunity to increase his authority in the region and put further pressure on the English king. English rule in Ireland was widely resented by the native Irish and Robert chose this moment of low English morale to offer the Irish a new deal, in alliance with Scotland. He sent over an army led by his brother Edward Bruce. Roger Mortimer rushed back to Ireland to defend his lands but was defeated at the battle of Kells in 1315. Though Dublin and a handful of castles, including Trim, held out against Edward Bruce, he was crowned King of Ireland on May 1st 1316.

Having returned to England following the battle of Kells, Roger distinguished himself as a soldier, both in helping to put down the rebellion of Llewelyn Bren in Wales and in the successful siege of Bristol. Recognising both his loyalty and his effectiveness as a military commander, Edward II appointed Roger to the post of King’s Lieutenant in Ireland, tasked with re-establishing English rule. After careful planning and many tiresome delays, he eventually landed in Ireland with a large army on 7th April 1317. An able commander and administrator, Roger was very successful, Edward Bruce being defeated and killed in October 1318 shortly after Roger had returned home.

All was not well in England. Over many years Edward II had given undue power at court to various ‘favourites’. This inevitably led to conflict with the senior earls and barons of the land. By 1318 one of these, Piers Gaveston, had already come and gone, captured, tried by a council of barons and summarily executed in 1312. However, the removal of Gaveston hadn’t solved the problem and by 1317 he had been replaced by new favourites including the wily and avaricious Despensers, father and son. Relations between Edward II and the earl of Lancaster were at an all-time low and Roger Mortimer had been called back from Ireland to help negotiate on behalf of the king. As part of the team that negotiated a peaceful settlement with Lancaster, Roger was chosen to be one of just four barons on the permanent royal council. In March 1319, he was sent back to Ireland, this time as Justiciar, to establish a stable peace and the rule of law. He was notably successful in this and, when he returned to England the following year, he won great praise from the Dublin authorities.

Roger was involved in raising Llywelyn Bren’s siege of Caerphilly castle

Hugh Despenser the Younger

By 1320 Roger Mortimer had come a very long way in a fairly short time. Now very rich, he had demonstrated his ability as a strong and effective leader and negotiator and his loyal service ensured that he was trusted by the king. The future must have looked very bright indeed for Roger, but there was one fly in the ointment that was going to turn his world upside-down and that fly was Hugh Despenser the Younger.

Despenser was cunning, ambitious and utterly ruthless. Having skilfully managed to secure a pre-eminent place at court as the king’s favourite, he exploited every opportunity for personal advancement at the expense of others and he particularly singled out Roger Mortimer. Roger was clearly a rival, but there was a deeper reason for Despenser’s hatred. At the battle of Evesham back in 1265, Roger’s grandfather had slain Hugh Despenser’s grandfather and this had not been forgiven. Despenser vowed to destroy Mortimer – and he almost succeeded.

As the younger Despenser’s influence grew he became more and more autocratic and high-handed. The turning point arrived when, with the acquiescence of the king, he began to acquire lands in south Wales that actually belonged to other people. In this situation, all the Marcher lords felt threatened, but they were in a very difficult position. Basically loyal by nature, any move against Despenser would effectively be an act of rebellion against the king. Between a rock and a hard place they reluctantly moved into active opposition. When Roger finally joined the other barons he was quickly stripped of his title as Justiciar of Ireland. His uncle, Roger of Chirk, also joined the rebels after 50 years of loyal service to the crown.

In May 1321 Roger led a large army to attack Despenser lands in south Wales, where they wreaked havoc. He then moved to London. Faced with overwhelming opposition, the king was eventually persuaded that he had no option but to exile the Despensers. It looked as if Roger had won his personal battle with Hugh Despenser the Younger. But, although the rebels had achieved their primary objective, they were now in a very difficult position and things quickly turned against them. The king greatly resented having to banish the Despensers and could not forgive the humiliation he had suffered. He was determined to revenge himself on the Marcher lords and mustered an army. With the the Despensers now out of the country, his loyal subjects no longer had any reason to refuse his demand. Roger and his uncle saw much of their support evaporate and on 22nd January 1322, they submitted to the king at Shrewsbury. Despite the two Rogers being assured that they would be pardoned, they were placed in chains and sent to the Tower.

Having captured the Mortimers, Edward felt confident enough to recall the two Despensers. He now set about dealing with the rest of the rebels, led by the Earl of Lancaster, and the two forces clashed at Boroughbridge in March. The rebels were defeated and the Earl of Lancaster summarily executed. Edward’s anger and vindictiveness knew no bounds and he set about hunting down and executing all those who had opposed him. In July, Roger and his uncle were tried in Westminster Hall and sentenced to death for treason. The Wheel of Fortune had turned once more: Hugh Despenser was up again and Roger was down and (almost) out. Edward II then made a mistake that was to have dire consequences for him later: he commuted the sentences of the Mortimers to imprisonment for life.

Westminster Hall – scene of Roger’s trial in 1322

The priory at Saint-Sardos,

a village in Gascony at the centre

of a short war in 1324

Basking in the warmth of the king’s affection and trust, Hugh Despenser was now unassailable; the king seems to have automatically approved everything he asked. His ambition knew no bounds and he set about increasing his wealth and influence further by fair means or foul. There was soon once again widespread dissatisfaction in the country but, aware of the dire fate of Lancaster, Roger Mortimer and the other rebels, opposition was necessarily sporadic and disaffection more muted.

Though incarcerated in the Tower, there is evidence that Roger still had significant support in the country and was seen as a potential saviour from the rule of Despenser. Things came to a head when, realising the potential danger, Despenser urged the king to execute Roger. Aware of the urgency of the situation, detailed plans were made by supporters to free him from the Tower. Queen Isabella certainly feared Despenser and hated what he was doing to her husband and to the country. She was ready to throw in her lot with Mortimer and was probably made aware of his impending escape. On 1st August 1323 the plans were put into execution. First it was necessary to get most of the guards drunk and then, with inside help, he was spirited from his cell, up and over the high walls of the castle and into a waiting boat. The escape had been well-planned and he was out of the country within a couple of days.

Roger made his way to Paris. This was an astute move as there was already tension between Charles IV of France and Edward II over Gascony and Roger was welcomed as an ally. Edward had so far failed to do homage to the French king for lands he held in Gascony and was failing in his duty to maintain law and order there. Moreover Charles was Queen Isabella’s brother and he will have been very aware that her situation in England was unhappy. Edward’s infatuation with Hugh Despenser meant that the queen was increasingly isolated. Just like Iago in Othello, Despenser worked to undermine the king’s trust in his queen. Because she had tried to argue against some of Despenser’s decisions, she was now suspected of being in league with Roger Mortimer. Her income was drastically reduced and other measures were taken to humiliate her.

Things were threatening to escalate out of control when Edward II eventually agreed to Charles’s subtle suggestion that Isabella should negotiate on his behalf. It was with great joy that she was able to leave England in March 1325. Throughout the negotiations there remained the thorny issue of Edward’s homage to Charles. Very reluctantly the king eventually decided to go to France, but Hugh Despenser feared for his life if the king left him alone in England. So the fateful decision was taken to send Prince Edward, the heir to the throne, instead. Alongside the Prince’s arrival in Paris came a firm demand from Edward that Isabella should return home immediately. But she was not so naive. Re-united with her son, accepted at the French court and with Roger Mortimer waiting in the wings, she stayed where she was.

One of the strict conditions Edward laid down before he allowed his queen to travel to France was that she should have no contact with ‘The Mortimer’ and certainly Roger was in Hainault in northern France when she arrived. There is no hard evidence that Roger and Isabella became lovers, but it seems highly likely. United by a strong desire to rid England of Hugh Despenser they worked together to plot his downfall. Potential supporters in England must have been encouraged as these two key people presented a united front. Though their key objective was the removal of the Despensers, Roger & Isabella came to accept that their actions would inevitably have much more serious consequences. An attack on Despenser was an attack on Edward himself and there is no way the king would have forgiven his queen or Roger Mortimer for removing his favourite. So for their own long-term security Edward II would have to go too.

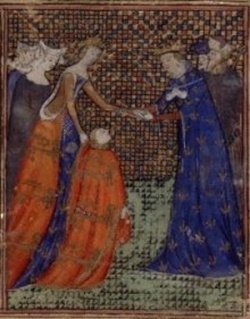

Prince Edward giving homage

to Charles IV accompanied by

his mother, Queen Isabella

Roger and Isabella on board ship

Roger and Isabella planned an invasion of England and a fleet was assembled with the help of Count William of Hainault. Before the final decision was taken, both sides made demands: Isabella insisted that Despenser should be exiled; Edward urged his son to leave Isabella and return to England; but nothing happened. Just before sailing, Roger heard that his old uncle, Roger Mortimer of Chirk had died in the Tower, while in the custody of Hugh Despenser. Failure to remove Despenser was to cost Edward his crown and maybe his life. On 24th September 1326, Roger and Isabella landed in Suffolk with possibly as few as 1100 men.

Edward didn’t see this small force of foreigners as much of a threat. He summoned the huge total of 47,640 men to take up arms immediately and offered a reward of £1,000 for Roger’s head. But Roger and Isabella played their cards well. Though Roger was the military commander, Isabella now took the lead and she presented herself as a religious and deeply-wronged queen coming with her son, the heir to the throne, to rid the country of the pernicious Despenser. It was the right approach and the numbers going to her aid grew rapidly. Edward’s great army failed to materialise and his support quickly evaporated. By late October the king was on the run with Hugh Despenser and a few retainers.

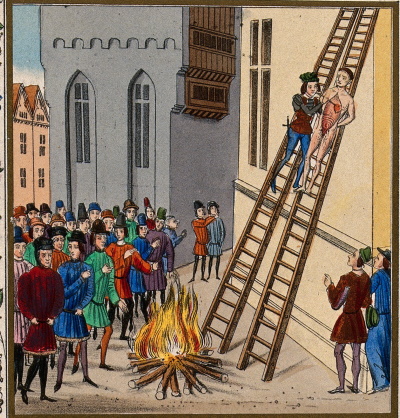

Now in complete control of the government of the country, Roger and Isabella appointed the 14 year old Prince Edward in his father’s place, a move that was generally acceptable in the circumstances. And now a bitter revenge could finally be exacted for the Despensers’ years of malpractice and self-aggrandisement. Hugh Despenser the Elder was executed at Bristol. His son was with Edward in Wales and they were eventually captured near Neath. Despenser was taken to Hereford where a tribunal prepared a detailed inventory of his misdemeanours. This almost endless list was read out in the market square before Roger and Isabella. He was then dragged to the castle to be dramatically executed. Tied to a high ladder, his penis and testicles were cut off and thrown into a large fire. His body was then cut open while he was still alive and his guts and heart removed and burnt. Then his head was cut off and his body cut into sections to be displayed in towns across the country. And so, in the ongoing vendetta between Roger and Hugh Despenser, the Wheel of Fortune had turned 180 degrees for the last time.

The death of Hugh Despenser the Younger

Effigy of Edward II on his tomb at Gloucester

There remained the difficult question of what to do about Edward II. While he lived, he would always be a focal point for rebellion, but to be seen to execute an anointed king would be equally hazardous. The first step was to officially depose him and Roger skilfully managed the legal process to achieve this. On 20th January 1327 Edward was led into the great hall of Kenilworth castle where he was imprisoned. After his crimes had been read out, he offered to abdicate in favour of his son. It is not known precisely what happened to Edward II after his abdication. He was transferred to Berkeley Castle and, not surprisingly, attempts were soon made to free him. Then on 21st September 1327 it was announced that he had died of natural causes and his funeral was held in Gloucester cathedral on 20th December. However, it was widely believed that Edward II had actually been murdered and Roger was the obvious suspect. Be that as it may, there is absolutely no evidence to support the popular story that Edward had a red-hot ‘poker’ shoved into his anus to avoid any external indication of murder, or possibly as a crude reference to his supposed homosexuality. This gory tale emerged much later.

But did Edward actually die at all in 1327? There is circumstantial evidence that he was moved from Berkeley to Corfe castle and that he then survived in secret exile on the Continent for a further 15 years. But why would Roger possibly prefer Edward to survive? While recognising the political necessity for him to be officially dead, neither Roger nor Isabella would have wanted the king’s blood on their hands. Isabella was a devout Christian and, after all, Edward was her husband. And Roger knew that he was only alive because Edward commuted the death sentence passed on him in 1322. All along their real enemy was Despenser, not the king.

Roger’s position after the coronation of Edward III is an interesting one. Queen Isabella was the official Regent and Roger was her friend, advisor and spokesman. This position gave him considerable autonomy and power and he was prepared to use it, often in opposition to the wishes of the other senior barons. As the king’s decisions and policies actually came from him, Roger was, in reality if not legally, the ruler of the country. But he had no official position and this made him vulnerable and was to contribute to his eventual downfall. Just as the barons had objected to the upstart Piers Gaveston and the wily Despenser, they soon grew tired of this man who increasingly behaved as though he was himself the king.

Crucially, the young king himself began to distrust and dislike Roger. Enmity between England and Scotland persisted after Bannockburn but, while still in France, Roger and Isabella had made an important agreement with the Scots. In return for an acknowledgement of Scottish independence, the Scots would not cause problems during the impending invasion of England by Mortimer and Isabella. But such a concession to Scotland was fiercely criticised by English lords once it became known, and the official ratification was postponed. Losing patience, the Scottish king planned an invasion. An English army moved north in July 1327 to counter the threat, with the young Edward III taking part in his first military campaign. Though the two forces never seriously engaged each other, the Scots killed several hundred English in a daring night-time raid and then withdrew back to Scotland. It was a humiliating experience and both king Edward and the northern barons blamed Roger personally for the situation and for the demeaning Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton that followed in 1328.

The stand-off between English and Scottish troops at

Stanhope Park before the surprise night-time raid by the Scots

Corfe Castle – was Edward II

imprisoned here after his ‘death’?

All this time, of course, Roger was married to Joan de Geneville. When Roger had been sent to the Tower in 1322, all his possessions were forfeit and his wife was imprisoned too. It was to be five years before Roger saw his wife again, during which time he had acquired a beautiful and powerful new partner. Joan seems to have accepted the situation philosophically, but it must nevertheless have been difficult for her when she was expected to entertained Isabella at Ludlow castle in 1329.

Roger had himself created Earl of March in 1328, a significant title as all previous earldoms had been of single counties. As the inevitable result of unbridled power, his arrogance increased and he began to ‘play the king’ more openly. Previously deferential towards Edward III, he now was seen to walk beside him, sit in his presence and insist that his word was obeyed rather than the king’s. He organised a great Round Table tournament at Wigmore. With his queen by his side, he had himself, rather than Edward, crowned as King Arthur, an attempt to pass himself off as a member of the royal family. His own son, Geoffrey, labelled him the ‘King of Folly’. Edward III would soon be 17. He was finding Roger’s arrogance and control increasingly irksome and looking for a way of exerting his own authority.

It has been argued that Edward III was made aware that his father was still alive soon after the king’s apparent interment at Gloucester. Certainly Edward II’s brother, the earl of Kent, believed it and Roger learned that he was plotting to free the ex-king from Corfe castle. His response was as tyrannical as Despenser’s had been: Kent was to lose his life and his family were to be disinherited. Though the sentence was shockingly cruel, the king felt he had no option but to agree. When it came to the earl’s execution on 19th March 1330, they had difficulty finding anyone willing to cut off his head.

Aware that his control over the young king would not last much longer, Roger now sought to enrich himself by every means possible. By claiming that his uncle Roger Mortimer of Chirk’s son was illegitimate, he even appropriated his cousin’s inheritance. Roger was now widely hated and the dénouement was not far away. When the end came, it came quickly. Parliament was meeting in Nottingham Castle in October 1330. The castle sits on top of a knoll of soft sandstone and several tunnels existed, linking street level below with the castle above. One of these actually emerged right inside the royal apartments. On the night of 19th October the castle was apparently secure and on high alert, but the existence of the tunnel was not widely known. The young king seized the opportunity to rid himself of Roger. He unlocked the door at the top of the tunnel enabling a small armed group of his close friends to enter the royal apartments. It took only a short time for Roger to be overpowered. Realising that this was her son’s doing, Isabella pleaded for the “gentle Mortimer” but to no avail.

Parliament met in London on 26th November to decide his fate. Like Hugh Despenser and the Earl of Kent, he was not allowed to speak. The 14 charges against him included taking royal power and government to himself; murdering Edward II; having himself created Earl of March; keeping other advisers away from the king; using his power to enrich himself; raising money through a parliamentary grant and then spending it himself; threatening to kill the queen if she returned to her husband and ordering that his word should be obeyed rather than that of the king. The verdict was inevitable. Three days later he was taken from the Tower and dragged nearly two miles through the streets before being hanged at Tyburn.

One of the man-made tunnels under Nottingham Castle

All Roger’s estates and titles were forfeit, so his son Edmund did not become Earl of March. His loyal wife, Joan, suffered greatly because of her husband’s actions. When he was arrested in 1322, she was imprisoned first in Hampshire. She then suffered great hardship when transferred to Skipton castle and was later moved to Pontefract, not being released until Roger and Isabella’s invasion in 1326. Although she was treated fairly leniently after Roger’s arrest in 1330, Joan was not pardoned till 1336 when she was given back many of her possessions. Her family castle of Trim was restored to her in 1347 and she eventually died in 1356 at the age of 70. Queen Isabella was never accused of any misdemeanours and was given a handsome income, dying in 1356.

So it was an ignoble end for a man who, for most of his life, had the best interests of his country at heart. Hugh Despenser was a sworn enemy of Roger and Edward II was guilty of giving him free rein to tyrannize the Mortimers and other Marcher lords. Largely a victim of circumstance, Roger rebelled to save his country. It was only in the last five years of his life, after he’d achieved his main objectives for his country, that things went badly wrong.