Roger Mortimer (d1282)

Slayer of Simon de Montfort

We come now to the Mortimer who first propelled the family to the forefront of national affairs. On the death of Ralph Mortimer in 1246, the lordship of Wigmore devolved on his son Roger Mortimer (d1282). Despite continually being at war, either in England, Wales or France, Roger survived everything and died a rich and honoured supporter, advisor and friend of king Edward I. We understandably tend to hear more about his famous grandson, Roger Mortimer (d1330) who rebelled against Edward II and ruled England with Queen Isabella, but the grandfather was a man of almost equal stature and significance in the history of England.

Before describing Roger’s life in detail it is worth drawing attention to one important aspect that was present for most of his adult life. As mentioned in the last article of this series, Roger’s maternal grandfather was Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (Llywelyn the Great) Prince of Gwynnedd, and perpetual foe of the two previous lords of Wigmore. Some years after the death of Llywelyn, his mantle was taken up by another of his grandsons, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. For years he fought to reclaim Wales for the Welsh and to achieve official recognition of himself as ‘Prince of Wales’. Roger Mortimer and his cousin Llywelyn were to be fierce enemies for most of their lives. A thorn in each other’s sides, they both died in 1282 but in very different circumstances. Roger died of natural causes greatly honoured by his king. By contrast, just six weeks later, in the area around Builth in central Wales, Llywelyn became separated from his main army, perhaps through trickery, and was murdered by a force that is said to have included Roger’s two sons Edmund and Roger. For the next 15 years Llywelyn’s head was on public display at the Tower of London.

Statue of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd above Llandovery

Orthez in Gascony, home of Gaston VII,

Viscount of Béarn and implacable foe of the English

Roger is thought to have been only about 15 when his father died in August 1246, but it was not long before he paid a substantial sum to the king to gain personal control of his lands, despite still being a minor. By the end of 1247 he had married Maud de Braose, seven years his senior and one of the four co-heiresses of William de Braose who had been hanged on the orders of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth in 1230, on suspicion of having slept with the latter’s wife. This marriage brought with it extensive estates including the lordship of Radnor and a share of the Brecon lordship as well as important lands in South Wales, England and Ireland and this greater wealth was an important factor in the rise in national significance of the Mortimers.

While king Henry III was holding court at Winchester in 1253 he personally conferred the honour of knighthood on Roger and later in that year he accompanied the king to Gascony. Back in 1248 king Henry had appointed the Frenchman Simon de Montfort as Viceroy of Gascony with a brief to bring some order to a lawless and unhappy region. Simon’s approach was extremely oppressive and many complaints were made against him. Though officially exonerated, Simon was dismissed in 1252 and the king’s expedition to Gascony was an attempt to to repair the damage done.

Returning to England, for the next ten years Roger was embroiled in serious unrest on two fronts. As well as the continuing problems with Llywelyn in Wales, he was completely caught up in the developing crisis between Henry III and his barons that was to result in the Second Barons’ War.

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was now flexing his muscles and becoming a significant threat and in 1256 he recaptured Gwrthrynion, the lordship to the north-west of Llandrindod, previously held by Roger. Alert to the threat of resurgent Welsh nationalism, Henry III made provision to strengthen his position and in 1258 Roger was promised substantial financial aid to continue the fight. Roger can’t have been very successful, however as, a year later, he was engaged in negotiating and signing a one-year truce with Llywelyn.

In England things were becoming very serious indeed. Despite the issue and re-issue of Magna Carta since 1215, the king still sought to exercise personal power over many areas without reference to his barons. As well as feeling the general disaffection, Roger had other, more personal, grievances. The money that king Henry had promised him to help fight the Welsh had never materialised and there had been protracted disputes over the Braose inheritance.

Matters came to a head in 1258 when Simon de Montfort called a great Council with the object of reforming the state. Called the ‘Mad Parliament’ it consisted of 12 nominees of the king and 12 chosen by the barons. The fact that the 27-year-old Roger was one of those nominated by the disaffected barons underlines the esteem in which he was held by his peers. This council’s deliberations resulted in the Provisions of Oxford which severely restricted the freedom of the monarch. The Provisions established a Privy Council of 15 to advise the king and exercise control over the administration. Roger Mortimer was one of the nine barons appointed to this permanent council. It is interesting to note that the disenchanted barons had a significant supporter in Lord Edward, the heir to the throne, who gave his approval to the Provisions of Oxford.

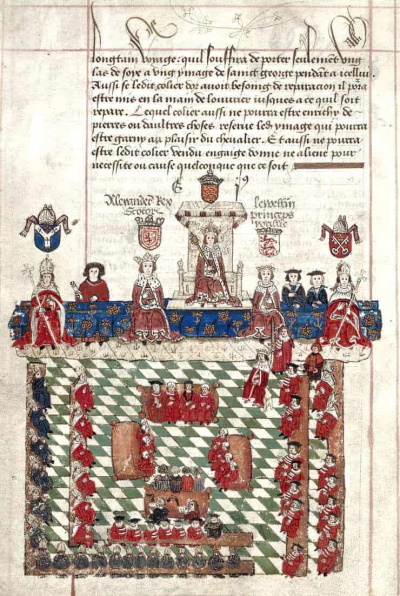

A rather fanciful impression of a council

presided over by Edward I

Site of the Mortimer castles at Cefnllys

In 1260, as soon as the year of truce was over in Wales, Llywelyn attacked and captured Builth Castle. Roger Mortimer held Builth for the Lord Edward, and he was partially blamed by the prince for its loss. Roger now found himself in an increasingly difficult position. An ambitious man, Simon de Montfort was developing an ever-closer rapport with Roger’s arch-enemy Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Montfort also quarrelled with Richard de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, who was one of Roger’s closest associates. Then the Lord Edward became reconciled with his father and abandoned the barons’ cause. With the barons divided, Henry took the initiative against the reformers. He revoked the Provisions of Oxford and forced the barons to compromise and accept his authority. Several of the key barons were pardoned by the king. Simon de Montfort retired to France to bide his time but, encouraged by financial inducements, Roger Mortimer moved onto the king’s side and was to stay loyal for the rest of his life.

Over the next few years things became increasingly tough for Roger. His Welsh tenants in Maelienydd rose in revolt, calling on Llywelyn, who attacked and captured several Mortimer castles including the great castle at Cefnllys near Llandrindod. In 1263 Simon de Montfort returned to England, gathering around him a group of discontented barons. When Henry refused to reinstate the Provisions of Oxford hostilities began again, the barons receiving support from Llywelyn.

1264 must have been the worst year of Roger Mortimer’s life and it now became very personal between himself and Simon de Montfort. Roger was seen as one of the rebels’ most dangerous opponents and, with Welsh help, they attacked his lordship of Radnor, besieged Wigmore and levelled most of his other castles.

At the national level things escalated and, despite being heavily outnumbered, Simon won a great battle at Lewes taking many prisoners including the king, Prince Edward and Roger Mortimer. He forced Henry to agree to new demands in a document called the Mise of Lewes and imprisoned the Lord Edward as a hostage for the king’s future behaviour. Simon made a big mistake, however, in allowing the royalist Marcher lords to return home to secure the Welsh border. Not surprisingly they ignored the Mise of Lewes and, infuriated, Simon moved against them. Mortimer lands were laid waste and in August he captured Wigmore castle. Roger eventually surrendered at Montgomery and submitted to Simon. So ended a terrible year.

Luckily things improved dramatically the following year. It has been suggested that it was Roger or his wife Maud who hatched a plan for rescuing Prince Edward. He was being held at Hereford castle but, apparently, was sometimes allowed out under supervision, to exercise. On 28th May 1265 he got permission to go out into fields away from the castle to race some horses. Edward got on a good fast horse and, at a signal from one of the waiting rescue party, he put spurs to his horse and just galloped off with them in the direction of Wigmore. His jailers at Hereford must have felt pretty stupid and one can imagine Simon’s reaction when he heard the news. Maud is said to have fed and watered him at Wigmore and then sent him on to Ludlow Castle…. How true a reflection this narrative is of Edward’s escape is not clear, but it certainly makes a good story.

The battle of Lewes 1264

De Montfort’s army advancing uphill in a thunderstorm

was overwhelmed by superior numbers and tactical advantage

Things had not been going all that well for Simon since the battle of Lewes and in August it came to a pitched battle against the royalist forces at Evesham. Prince Edward had greatly superior numbers and the rebels were finally defeated. Roger Mortimer fought his way through the crowd and personally killed Simon de Montfort. He then sent the severed head to Maud at Wigmore. There is a story that she organised a big party and displayed Simon’s head on a pike in the Great Hall with his testicles in his mouth.

Mopping up the opposition to the king took a further couple of years, with Roger at the centre of events. He was rewarded for his loyalty with lucrative new posts and estates, some of which had been forfeited by the rebels. Some of the victors took a conciliatory line, counselling mercy for the disinherited rebels and the early restoration of their lands, but Roger strongly opposed this policy, fearing the loss of his newly-acquired estates.

Nearer in age to Prince Edward than he was to the king, they remained close friends for the rest of his life. When Edward went on crusade in 1270 he named Roger as one of five people appointed as guardians of his children and his interests. Henry III died in 1272 while Edward was still in Palestine and Roger was one of a small group who acted as regents until his return in 1274.

The Barons’ War and its aftermath in England had, to a large extent, diverted attention away from what had been happening in Wales. Back in 1266 Roger had attempted to retake Brecon, only to have his army completely annihilated by Llywelyn. A year later Henry III decided to accept the situation and come to terms with Llywelyn. By the Treaty of Montgomery he received the homage of Llywelyn and formally acknowledged him as Prince of Wales, a title that had never previously been recognised. However, on his return to England, Edward I took a much harder line with Llywelyn and in 1276 he declared him a rebel and moved against him. Roger commanded the army that struck into the centre of Wales, capturing Dolforwyn castle. Indeed, for the rest of his life, Roger Mortimer was in the forefront of the fight against his old enemy and he was well-rewarded with new lordships.

By the year 1279 Roger was becoming an old man and he was given the great honour of being allowed to organize a grand tournament at Kenilworth castle. Writing in 1852 Thomas Wright says:

‘After his sons had been knighted by king Edward I, Roger held a great tournament at Kenilworth and a ’round table’, entertaining sumptuously for three days a hundred knights, with as many ladies, at his own expense; and having himself gained the prize of a lion of gold, on the fourth day he carried all his guests to Warwick. As was the custom, the tournament had been proclaimed in foreign countries and the fame of Roger’s gallantry was spread through distant lands. The queen of Navarre is said to have fallen in love with him, and to have sent him wooden flasks of wine, bound with gilt hoops and wax which, when opened, proved to be filled, not with wine but with gold. These ‘flasks’ were long preserved in the abbey of Wigmore: and for the queen’s love Roger de Mortimer added a carbuncle to his arms for the rest of his life.’

Roger took part in Edward’s 1282 campaign against Llywelyn, being in charge of operations in mid-Wales. He became ill in Kingsland and was buried at Wigmore Abbey, much lamented by the king. Writing to Roger’s son, Roger Mortimer of Chirk, king Edward I says……

‘As often as the king ponders over the death of Roger’s father he is disturbed and mourns the more his valour and fidelity and his long and praiseworthy services to the late king and to him recur frequently and spontaneously to his memory’

A moving tribute to an old friend and comrade.

Olympic cycling champion Victoria Pendleton tries

modern-day jousting at Kenilworth castle