Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March

A Royal Wedding with far-reaching Consequences

In this series of articles we have already met several larger-than-life Mortimers. Four Roger Mortimers immediately spring to mind: Roger (d.1282) who killed Simon de Montfort at the Battle of Evesham; his son Roger of Chirk, another great warrior who ended his days in the Tower; Roger, 1st Earl of March, executed for treason in 1330 and his grandson Roger (d.1360) who managed, in his short life, to completely rebuild the family fortunes. It can reasonably be argued, however, that it was Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March who was to leave the greatest legacy, though he can take little credit for it. His father, the 2nd Earl of March, achieved much in his short life, and there can be no greater evidence of the rehabilitation of the Mortimers than the betrothal of his 6-year-old son, Edmund, to a royal princess. Just 28 years after he had executed the 1st Earl of March, king Edward III agreed to the marriage of his own granddaughter into that same family. Consequently all the future Earls of March had royal blood, and it is this marriage which was to form the basis of the House of York’s claim to the throne during the Wars of the Roses over 100 years later.

In 1368, at the aged of 17, Edmund married Philippa, the only child of Lionel, 2nd surviving son of King Edward III. By this time Philippa had inherited from her mother the title of Countess of Ulster. His father having died when he was just eight, Edmund was now styled ‘Earl of March and Earl of Ulster’. Despite his youth he was made Marshal of England and was employed on various diplomatic missions. Having already been on campaign in France in 1369, he took part in another expedition in 1372, leading a force of 19 knights, 60 esquires and 120 archers. This proved a humiliating failure. Things did not improve for him when, in 1375, he was involved in an expedition to support the Duke of Brittany against the French king. Shortly after the arrival of the English, a truce was agreed between the two sides and the English had to set off home again. These campaigns proved very costly for Edmund and reimbursement from the king was slow in coming.

Carrickfergus – the birthplace of Philippa’s mother

Elizabeth de Burgh, 4th Countess of Ulster

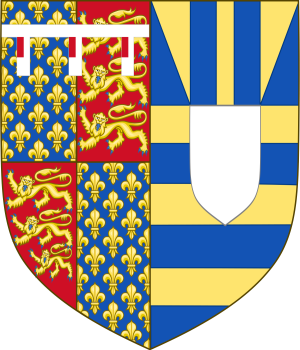

The royal arms of Philippa impaled with those of her husband, Edmund Mortimer. The small red rectangles (cantons) on the white label tell us that she was descended from Lionel, 2nd son of Edward III

The arms of John of Gaunt’s wife, Constance of Castile, impaled with the royal arms. Note that John of Gaunt’s arms, on the right, are differenced from those of his brothers by having an ermine label

In post-conquest England, the monarch consulted with a Great Council consisting of earls, barons and senior clergy, the main pillars of the feudal system. But increasingly over the 13th and 14th centuries, knights of the shires were also commanded to attend these parliaments, and these “commoners” came to exercise a growing influence. The “Commons” met separately from the “Lords” for the first time in 1341 and it was established that no law could be passed or tax levied without the consent of both houses of parliament and the sovereign.

After a long, energetic and largely-successful reign, Edward III was now aging. Disaffection had spread through the country, the court party around the king being recognised as corrupt and inefficient. The main power behind the throne was John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the king’s 3rd surviving son – not a man it was easy to stand up to. Aware of the general atmosphere of criticism in the country, the king and his advisors had not called a parliament for several years. But the royal treasury desperately needed filling and, as taxes could only be levied with the agreement of parliament, they now had no choice but to call one. The parliament of 1376 has been called the Good Parliament. Although its main purpose was to agree a new round of taxation, it was seized upon by disgruntled lords and commoners as a golden opportunity to introduce much-needed reforms.

Opposition to the Lancastrian dominance at court was led by Edward, Prince of Wales, the Black Prince. Edmund Mortimer was firmly in the reform camp, allying himself with the prince and other disaffected peers, and with the Commons. This set him on a collision course with John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. So began an antagonism between the Mortimers and the Lancastrians that was to resound through English history for over a hundred years. Edmund was no minor figure who could be easily ignored or manipulated: though only 24 he was probably the greatest landowner in the country after the king and John of Gaunt. His Mortimer inheritance included estates in Wales and the Welsh borders (in Monmouth, Brecon, Radnor, Herefordshire, Shropshire, Montgomery & Denbigh) but also estates in East Anglia and Ireland. Through his wife, he had also acquired the extensive earldom of Ulster making him one of the greatest landholders in Ireland.

That Edmund was recognised as a prominent member of the opposition is made clear by the fact that the Commons elected Edmund’s steward, Peter de la Mere, as Speaker. In his opening speech de la Mere criticised recent military failures and directly accused members of the king’s inner circle of corruption. He demanded that the royal accounts should be made available for scrutiny and summoned Richard Lyons and Lord Latimer, key members of the ruling elite, to appear before the Commons; both were subsequently imprisoned. Early in the parliament, Edmund was one of a group of peers selected to liaise between the Lords and Commons and later was one of the council set up to control the court.

For all its reforming zeal, the Good Parliament proved remarkably ineffective. Though most of their demands were acceded to by the government, they still refused to authorise any fundraising, and this lost them the support of the Lords. When the parliament broke up after more than three months, things quickly returned to normal. The Black Prince died in June 1376 and, with the king’s final illness now upon him, Lancaster wielded more power than ever. Lyons and Latimer were pardoned while the Commons Speaker, Peter de la Mere, was imprisoned. Without support from the Lords, the Commons were powerless to resist, as the decisions taken by the Good Parliament were reversed. When he forced through England’s first ever poll tax, public antagonism towards Lancaster increased to fever pitch. There was rioting in London and he feared for his life. Presumably to get him out of the way, Edmund, as Marshal of England, was ordered to inspect Calais and other remote royal castles. Rather than do this, however, he resigned the position.

The tomb of the Black Prince at Canterbury

William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester and Chancellor of England. His friendship with Edmund, Earl of March, sand support for the reformers, brought him into direct conflict with Lancaster. After the end of the Good Parliament, he was charged with financial irregularities and banished from court, but was rapidly pardoned by Richard II on his accession. He founded Winchester College and New College, Oxford.

The king’s death in 1377 completely undermined the power of the court party. The new king Richard II was only ten but, rather than appoint the distrusted Lancaster as regent, the lords established a succession of regency councils. Despite his wife’s family closeness to the crown, Edmund avoided seeking any special status and appears to have been content to play his part as just a member of the council. In the next couple of years he was very much occupied with Anglo-Scottish affairs, inspecting border castles and negotiating with the Scots.

As well as the ongoing war with France, the council had to do something about the deteriorating situation in Ireland. Originally granted their Irish lands by the English crown, over the years the Normans who had settled in Ireland increasingly resented being expected to put English interests first. Many of them adopted the Irish language and identified as Irish themselves becoming ‘more Irish than the Irish’. As well as the disruption caused by warfare among themselves, these Hiberno-Normans suffered much from the effects of the Black Death and successive famines. Edmund’s father-in-law Lionel, Duke of Clarence, had been Edward III’s Lord Lieutenant in Ireland in the 1360s. Sir William Windsor had signally failed to achieve much in his time as Lieutenant and in 1379 Edmund, 3rd Earl of March, was appointed to the role. It is not clear to what extent this move was engineered by the unpopular Lancaster to get him out of the way. Certainly, Edmund was well-qualified: adding together the Mortimer estates acquired through various marriages, and his position as jure uxoris Earl of Ulster, he was the major landowner in Ireland. Indeed other English settlers had requested that he be appointed, as early as 1373.

He arrived in Ireland in May 1380 and apparently made a very successful start. But we’ll never know how effective he might have been: after only 18 months in the role, he was taken ill and died in Cork in December 1381, at the age of 29. His eldest son, Roger, was just 7 at the time – another minor to add to the growing list.