The first two Mortimers of Wigmore

Ralph Mortimer (fl.1075-1115)

Hugh Mortimer (fl.1127-1181)

fl. = floruit or flourished = known to be alive

In the first part of this brief history, it was recorded that the ancestor of all the Mortimers of Wigmore, and the first to be called Mortimer, was Roger de Mortemer of Mortemer-en-Bray in Normandy. The first member of the Mortimer family to reside for any length of time in England was Roger’s son Ralph (or Ranulph) Mortimer (fl.1075-1115). It is not clear when he arrived in England, but apparently there is an account of him assisting King William in dealing with troublesome natives in the 1070s. In the Wigmore Chronicle, he is credited with capturing the rebellious Anglo-Saxon former magnate, Eadric the Wild. Ralph was certainly well-rewarded for his support and was given extensive estates, beginning with Worthy in Hampshire and Hullavington in Wiltshire. Soon afterwards he acquired Wigmore Castle, which had been built by William fitzOsbern (d.1071) and forfeited by William’s son Roger, earl of Hereford, on account of his rebellion in 1075. This became the chief seat of the Mortimer family for the next 350 years. By the time of Domesday (1086), Ralph held more than a hundred manors in England, distributed over twelve counties.

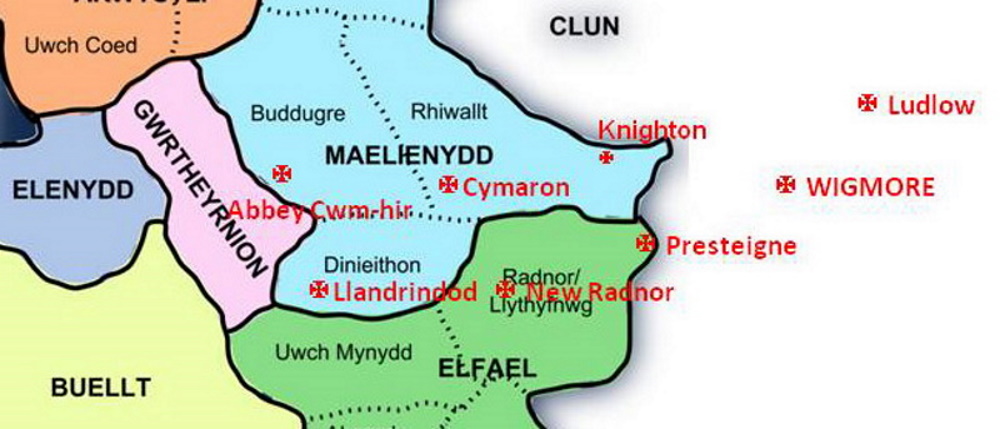

Welsh lordships close to Wigmore

Ralph founded a college of priests at Wigmore Church (consecrated in 1105) but retained a close association with his Continental estates. Indeed, he seems to have retired to Normandy in later life, there being very few references to him in England after 1100. Ralph died between 1115 and 1127, almost certainly in Normandy.

Ralph’s son Hugh Mortimer (fl.1127-1181) lived for such a long time that, until recently, it was thought that there were two of them, father and son. He seems to have grown up in Normandy, apparently not coming to live in England until some time after the death of his father. His early years as lord of Wigmore coincided with the Anarchy, the time of civil war following the death of Henry I, when Stephen and Matilda were fighting each other for supremacy. Hugh supported king Stephen rather than Matilda and became the leader of the royalist faction in the region. This brought him into direct conflict with Miles, Earl of Hereford and Josce de Dinan, the holder of Ludlow Castle who were supporting Matilda. Josce managed to capture Hugh at one point and imprisoned him in Ludlow castle, demanding a huge ransom.

The earls and barons with estates located along the Welsh border were given a fairly free hand to invade, subdue and then take over adjacent parts of Wales. These Marcher lords enjoyed considerable independence from the English monarch, so increasing their estates at the expense of the Welsh was an attractive proposition. At the same time their Welsh holdings acted as a protective buffer for their English estates along the border. Incursions into Wales began fairly soon after the Conquest. In 1093 Ralph joined a Norman force including the Earl of Shrewsbury and Philip de Braose in a campaign in central Wales and built castles including Cymaron, which was then held by the Mortimers for a short time. The area of Wales directly east of Wigmore, including Llandrindod Wells, was called Maelienydd and over the years it was fought over several times as Welsh fortunes ebbed and flowed.

The beautiful site of Cymaron Castle

This must have been paid as Hugh was subsequently a free man again. There is a small gatehouse tower in the curtain wall of the outer bailey in Ludlow Castle called ‘Mortimer’s Tower’ indicating the supposed place of Hugh’s imprisonment. As the outer bailey was not built till the second half of the 12th century, however, this must be incorrect. Around this time he advanced into Wales, re-conquered Maelienydd, which had been lost, and rebuilt Cymaron castle. During the disruption and lawlessness of the Anarchy, many formerly royal castles were either granted by Stephen to his supporters or just taken over by barons. One way or another, Hugh Mortimer acquired the castle at Bridgnorth between 1138 and 1140. Having supported Stephen, he was understandably not particularly well-disposed towards Matilda’s son, Henry II, when he came to the throne in 1154. The following year King Henry demanded the return of all estates and castles that had been royal property in the time of King Henry I, refusing to recognise any grants that King Stephen may have made. Hugh was told to relinquish Bridgnorth Castle but refused. The king laid siege to Bridgnorth and the Mortimer castles at Wigmore and Cleobury Mortimer and Hugh eventually had to submit. He was allowed to retain Wigmore and the (now almost destroyed) castle at Cleobury Mortimer.

In the early 12th century, great churches were being built in the Romanesque style at many places in England. Some of these churches, including those at Reading Abbey, Tewkesbury Abbey and Hereford Cathedral, exhibited sculptural decoration of a most varied and often flamboyant kind. Aspects of these sculptures have been linked to work in western France, Ireland, Scandinavia, Italy and Santiago de Compostella, but also with earlier Celtic and Anglo-Saxon art in England. Initially this exuberant and costly sculpture seems to have been largely restricted to the great churches, but in Herefordshire something special happened. A group of cultured men, probably including Robert de Bethune, Bishop of Hereford (1131-48) sought to apply this new style to much humbler places of worship. So was created the famous Herefordshire School of Romanesque Sculpture that thrived in the middle Marches in the 12th century. There are many outstanding examples of their work remaining, their carvings displaying an eclectic mix of styles, with Kilpeck church as the prime example.

Hugh Mortimer’s steward was called Oliver de Merlimond. He was an able and cultured man and he encouraged Hugh to patronise the Herefordshire School. Examples of their work are still to be seen at the Mortimer properties at Orleton, Pipe Aston, Rock, Ribbesford and Alveley. Hugh granted Oliver the manor of Shobdon, not far from Wigmore in Herefordshire where Oliver began to build a church. A visit to Santiago de Compostella in Spain will have done nothing to cool his enthusiasm for the new style. He incorporated it in the priory he went on to build at Shobdon. Little remains of Oliver’s priory church but, when it was pulled down in 1756, the chancel arch and two other arches were set up at the top of a nearby rise as a folly. Shobdon Arches still retain their Herefordshire School carvings but they are now badly eroded.

During the Anarchy, life wasn’t easy for the Augustinian canons of Shobdon. Exactly what happened is not clear as there are conflicting stories. Oliver de Merlimond changed his allegiance and began to support Matilda. This made him Hugh’s bitter enemy and, in his anger, Hugh not only took back Shobdon but, for a time, he seems to have reclaimed the gifts he had made to the priory, leaving the canons destitute. He subsequently relented and made new grants for their wellbeing. Shobdon lay at the very south of the Mortimer lands and therefore was vulnerable to attack by Matilda’s supporters in the south. It may have been for their safety that Hugh moved them further north. Over the next few years they settled at several places in the area before Hugh finally established them on a new site a mile or so north of Wigmore and upgraded the priory to an abbey. The foundation stone of Wigmore Abbey was laid in 1172 and the church consecrated in 1179. Little now remains of this important abbey that was the burial place of generations of Mortimers.

Only ten years after Hugh had rebuilt Cymaron castle in Maelienydd it was retaken by Cadwallon ap Madog and a personal feud seems to have developed between the Cadwallon and the Mortimers. In 1179 Cadwallon was called to court by Henry II to answer charges about disturbing the king’s peace. Returning to Wales under a safe conduct from the king he was ambushed and killed. The attack on Cadwallon was instigated by Hugh’s son Roger. By now a very old man, Hugh had at least some of his lands confiscated, but the consequences for his son were much more serious as he was imprisoned in Winchester.

It is not known for certain exactly when Hugh died. The financial records of the Exchequer (the Pipe Rolls) note that from 1181, his son Roger became responsible for his father’s debts. One chronicle states that Hugh resigned his lands to his eldest son and became a canon of Wigmore Abbey, dying in February 1185. Whether he died in 1181 or 1185, the earlier year marks the termination of his active life; he was buried in the church of Wigmore Abbey.

Eardisley, Herefordshire

Shobdon Arches

Wigmore Abbey